Better Is The Enemy of Good Enough With Crime Data

Just How Reliable Is The FBI's Quarterly Data?

"In his writings a wise Italian

Said that the best is the enemy of the good" - VoltaireI’m a big Washington Nationals fan, and in the absence of a hugely competitive baseball team1 I have taken to following the team’s top prospects in the minors. My favorite prospect to follow is James Wood, a mammoth outfielder currently eviscerating the minor leagues as he awaits his impending call up to the big league team.

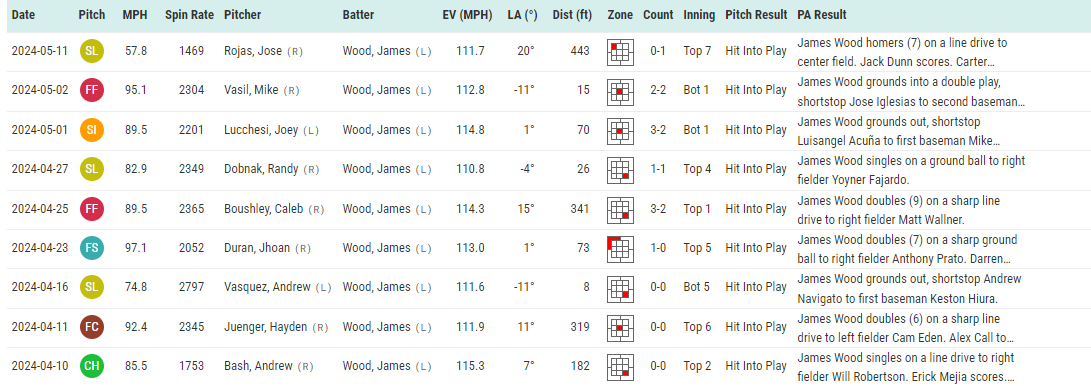

The other day Wood smoked a homer which left his bat at more than 110 MPH, a feat he has done nine times time (second most in all of AAA). Wood has hit three balls with an exit velocity of 114+ MPH, something that has only been done 15 times by other AAA players this season. If I want to I can pull up every pitch Wood hit at 110 MPH or more this season and see every detail about each pitch. Here they are thanks to Baseball Savant!

And then I can show that Wood’s average exit velocity is the best in AAA this season (minimum 250 pitches) while his strikeout percentage is in the bottom third of the league (that’s good!).

The Nats will call up Wood in the next few months and if he can give the big league club a spark and the starting pitching holds up… wait, this is about crime data. The point of this slightly off topic opening is to highlight the depth and precision of data surrounding baseball, even at the minor league level. That’s some obscenely precise data delivered almost immediately. As a baseball fan I’m very appreciative, but as a crime data analyst I’m jealous.

Precision that is anywhere near the same…ballpark…is sadly impossible with respect to crime data. I was reminded of this point in a recent assessment of crime data from something called the Coalition for Law Order & Safety (I’d link to their website or any other official documentation if I could find anything) which — among other things — argues that “official crime data likely significantly underreports crime levels, and most concerningly that recent NIBRS data is even more susceptible to this phenomenon making misreported crime data into misleading crime trends.”

The problem I have with the above assertion is that identifying the flaws that prevent precision from being possible should not detract from the reasonably accurate trends the data identifies. I’d take issue with the second half of the above statement, that NIBRS data is even more susceptible to reporting errors was certainly true in 2021, but the FBI allowed non-NIBRS agencies to submit data in 2022 (and 2023), and participation was largely in line with previous years in 2022 (93.5 percent in 2022 versus 95.2 percent in 2020). NIBRS makes an easy boogeyman, and in 2021 it was an actual boogeyman, but our understanding of crime trends in 2022, 2023 and 2024 is not really hampered by the NIBRS switch.

So the main issue is whether crime data is being incorrectly reported to such a degree to which it misrepresents the trends. As evidence, CLOS cited flaws in the FBI’s quarterly data that they identified by comparing year end 2022 and 2023 data in 40 cities in the quarterly data and the Major City Chiefs Association’s 2023 report.

To me though, the question is not whether the data is flawed — it undoubtedly is! — but whether the flaws in the data overcome the trends suggested by the quarterly data and other available sources. Table 4 of the quarterly crime data has data for cities over 100,000 that reported data. This table has had obvious issues since the time that 1 murder in a quarter was reported in Chicago (that was the last time Chicago reported quarterly data).

As I noted a few weeks ago, the quarterly data isn’t completed. I wrote: “the FBI data is preliminary, so take the information with the proper grain of salt (crime data should always be served with a grain of salt). Agencies still have some time to report 2023 data to the FBI, so these numbers are by no means final and will undoubtedly change a bit between now and October.”

The data is also unaudited which undoubtedly leads to many of the quality problems. I grabbed publicly available murder data for 161 cities that reported quarterly data to the FBI. Murder was down 13.6 percent in the FBI’s sample and down 10.7 percent in that same set of city’s public data. There are 38 other cities — like Chicago, Los Angeles, and New Orleans — that we have publicly available data for but that did not report quarterly data to the FBI. If we throw those cities into the sample then we get about an 11 percent decline in about 200 cities over 100,000 versus about 13.5 percent decline in the FBI’s sample.

Most cities in the FBI’s quarterly data are relatively close to their publicly reported figures. About 80 percent of cities were within 2 murders of their publicly available reported totals (126 of 161). Fort Worth, Texas reported 82 murders in the FBI data compared to 85 murders publicly as an example of a city that was close but not quite right. This difference could easily be due to additional murders being added after the data was submitted to the FBI.

There are other cities like Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Tulsa that had substantial undercounts for both 2022 and 2023 that suggests they didn’t yet report a full year for either year and the quarterly data may only reflect 9 or 10 months of data. One of the flaws in the quarterly data is that it doesn’t tell us how many months of data each city reported.

Then there are cities with obvious, unexplainable errors for 2022 and/or 2023. The FBI reported 338 murders for New York City in 2023 compared to 386 reported publicly. There’s Washington, DC which reported 261 murders in quarterly data compared to 274 murders. There’s Virginia Beach which had 9 reported murders in 2023 per the FBI compared to 23 reported publicly.

We’ve seen that the data has flaws and I’m guessing that those flaws are probably relatively common across smaller agencies as well (though they may have less of an impact on the overall numbers since there are fewer crimes there). I would expect that the 6 percent decline in violent crime and 13 percent decline in murder reported in the Q4 quarterly data will overstate the final reported national trend when we see it in October.

The quarterly data did the same thing in 2020 with the final quarterly data release showing a 25 percent increase compared to a 29 percent increase shown in the FBI’s final data release in October. That doesn’t mean that there wasn’t sufficient evidence to call 2020’s increase a large spike though (here’s me in February 2021 doing just that).

Quarterly data isn’t useful because it’s perfect, rather it’s useful because it effectively outlines the contours of the nation’s crime trends.

I wrote a few weeks ago that “the quarterly data paints the picture of a historically large decline in murder accompanied by smaller reported declines in violent crime and property crime in the United States last year.”

If we assume that the quarterly crime data for Q4 are overstating the decline in violent crime by 1 or 2 percent and murder by 3 or so percent when the final figures are presented then the assessment of national crime trends would still be that 2023 featured a historically large decline in murder accompanied by smaller reported declines in violent crime and property crime.

The FBI may report a smaller decline than 13.2 percent in the Fall, but the available evidence still strongly points to that figure being pretty substantial whatever it is. If that assessment was solely based on the quarterly data that would be one thing, but publicly available data from over 200 cities, data from the Gun Violence Archive, data from State UCR programs themselves, and data from the CDC all tell the same story of steadily declining murder in America.

Quarterly crime data is a new thing for the FBI to produce. Its value does not come from precision but rather from providing an accurate picture of crime trends that is inherently imprecise.

It’s certainly more than fair to acknowledge the flaws in crime data collection and reporting (that’s a running theme of this newsletter!). It’s wise to account for those flaws in expressing uncertainty when talking and writing about crime data. It’s good to identify errors and inconsistencies in crime data so they can be fixed. Even “final” crime data as reported by the FBI is an estimate based on incomplete data.

But it’s less useful to expect a level of precision in the data that is unlikely to be met and use the reporting’s flaws as an excuse for ignoring reasonably clear trends coming from multiple data streams.

Though they have been spritely this year!

Jeff

Great piece on the limitations of the available data! I found CLOS website: https://www.coalitionforlaworderandsafety.com/

To me though, "the question is not whether the data is flawed — it undoubtedly is!" , but is the flaw intentional of induced by incompetence. The incompetent should be trained, the intentional should be slapped... into jail.