An Overview of US Crime and Policing Trends

Where things stand heading into the first week of November 2024.

The election is next week so I thought it might be useful to create a primer of all the major trends on crime and policing that I have been following. These are not the only crime trends, but these are the trends that jump out the most in my opinion.

Overview

Murder is declining at the fastest rate ever recorded in the United States while violent and property crime remain at the modern low levels experienced for most of the last 10 years. Evidence from multiple sources point to declines in both violent and property crime in 2024 while the decline in murder is accelerating this year after falling at a record rate in 2023.

This assessment paints a comprehensive picture of US crime and policing trends based on data from multiple sources, including: FBI reported offense data, data collected through the Real-Time Crime Index, the CDC, the Gun Violence Archive, the National Crime Victimization Survey, and more. Crime data is imperfect and imprecise, but using a variety of sources allows for an accurate understanding of crime trends.

Murder

Murder is currently falling nationally at the fastest rate ever recorded after surging at the fastest pace ever recorded in 2020 Multiple sources of crime data point to this trend leaving little doubt as to its veracity. Murder rose 30 percent in 2020, came down slowly by 2022, and fell very rapidly with an estimated 11.6 percent decline in 2023. The available data for 2024 points to an even larger decline occurring this year that would put the nation's murder rate back at roughly where it was in 2019 before the surge.

The below graphs show the number of murders and murder rate nationally since 1960. Note that I am including the FBI’s 2021 estimates even though these were substantially impacted by the NIBRS transition.

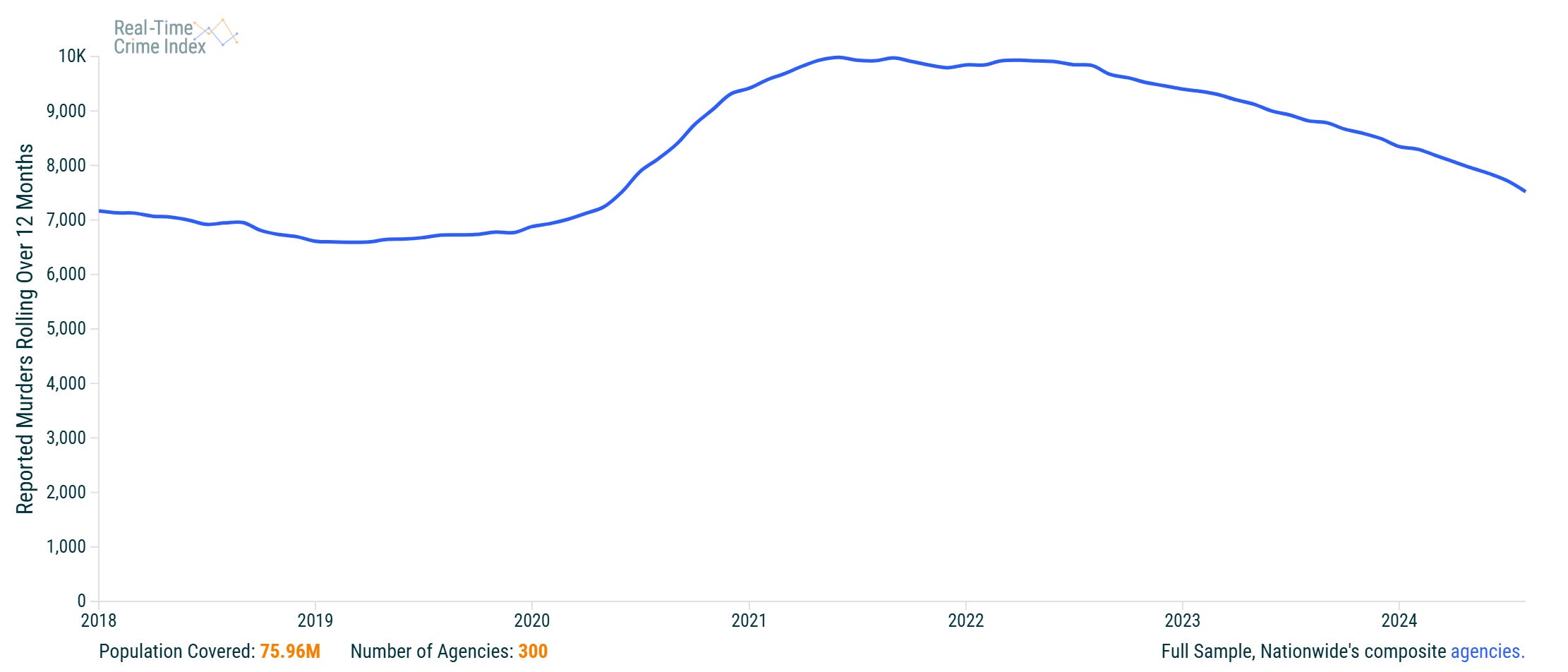

The assessment of plunging murder is not solely reliant on FBI data. The Real-Time Crime Index (RTCI) sample of 300 cities put murder down more than 10 percent in 2023 relative to 2022 and down 16.6 percent through August 2024 relative to the same timeframe in 2023. This sample makes up around 45 percent of the murders that will occur in a given year and largely mimics the FBI’s estimates.

Note that the most recent data point through August 2024 is measuring murders in the sample between September 2023 and August 2024. Extending the 2024 trend another four months through December would place this year's total roughly in line with 2019's though the exact figures remain to be seen.

Similarly, the CDC shows a sizable decline in homicides in 2023 with an even larger (13.3 percent) drop in homicides YTD through March 2024 (the CDC has only three complete months for 2024 published so far, and the 2023 and 2024 data from the CDC is provisional at this point).

There’s also the Gun Violence Archive showing a drop last year and a 12.5 percent decline in shootings this year through October relative to the same timeframe in 2023.

The same trend is seen when digging down to gun violence at the city level of many cities. Below are shooting victims rolling over 12 months in New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia which largely mimics the trends being seen in every other source.

All of these measures point to a rapid decline in murder and gun violence nationally last year and an acceleration in 2024. The FBI’s most recent estimates put the murder rate about 10 percent higher in 2023 than it was in 2019, so the current trend should place the US murder rate roughly at or below where it was in pre-COVID by the end of 2024 should the trends we have been seeing so far continue through the end of the year.

The decline in murder has been quite widespread. Murder was down in 35 states in 2023 compared to 2020 with a double digit percent decline in 25 states. Murder declined in 28 of the 37 states (76 percent) that reported at least 100 murders in 2020.

Murder is not down everywhere, but murders was down through August 2024 compared to the same timeframe in 2020 in 28 of the 34 cities that had at least 35 murders through August 2020. Murder was down 24 percent in Chicago through August 2024 compared to the same timeframe in 2020. It was down 39 percent in Philadelphia, down 42 percent in St Louis, 29 percent in Phoenix, 32 percent in Fort Worth, and 80 percent in Boston.

The below map shows the change in murders between 2020 and 2023 for every state in the FBI’s estimates. I’m using totals rather than percent change for murders because low base rate states with large percent changes skew the colors otherwise. I used percent change for violent crimes (further below) which are less prone to skewing because there are more violent crimes.

A couple of data notes: I used data from Pennsylvania’s state UCR program rather than the FBI’s estimations for that state due to reporting issues in 2020, see footnote1 for more details. I also removed Georgia from this map and the FBI violent crime map due to the estimates from the FBI for 2020 not matching what the state produced and having questions about both sources. See footnote2 for more details.

The Real-Time Crime Index shows the trend accelerating into 2024 through August. Murder was down by double digits relative to the first 8 months of 2023 in 34 cities while it is up by double digits in just 4 cities over that span (Long Beach, CA, Louisville, Charlotte, and Colorado Springs). The RTCI has data from 29 states that reported at least 25 murders through August 2023. Murder is down in 26 of those states, even in one, and up in two.

Overall, murder was down in 2024 compared to 2020 in 24 of the 29 states with 25+ murders through August 2020 in the Real-Time Crime Index supporting the large decline in murder reported by the FBI.

Simply put, murder and gun violence are plunging regardless of the source used. The FBI’s estimates say this, the CDC says this, the Gun Violence Archive says this, NORC’s Live Tracker says this, Major Cities Chiefs says this, the Council on Criminal Justice says this, and the Real-Time Crime Index says this. The historic decline in murder since 2020 is large and widespread throughout the country with the only uncertainty attached centering around how big it will end up being when all is said and done.

Violent Crime

I spent a lot of words on murder because it is a) the crime with the highest societal cost, b) the crime that has changed the most since 2020, and c) the crime trend that we have the most confidence in. Reported violent crime increased in 2020 though the increase in overall violent crime was much more muted than the increase in murder.

The FBI's recent revisions do not impact the understanding of current crime trends for a number of reasons: the revisions largely impacted 2021's counts and those estimates remain highly inaccurate due to being derived from under 75 percent of the country’s population (no LAPD or NYPD and only 6 months of Chicago data), a similar sized revision of 2023's figures along the lines of what was applied to the 2022 estimates would soften the decline but would not change the trends, and the assessment of current crime trends comes from multiple sources, not just the FBI estimates.

I’ve previously written about why the 2021 estimates require an asterisk and why the FBI’s methodology would likely to produce a dramatic undercount for that year (but not subsequent years), so read those pieces if you’re interested to know why I don’t give much credence to the impact of the FBI’s revisions on US crime trends. The best approach to the FBI's 2021 data remains to ignore it.

Ignoring 2021’s flawed estimate, the nation’s rate of reported violent crime in 2023 was virtually tied with 2014 for the lowest violent crime rate reported since 1970. And that’s not even accounting for a large human error in one agency which artificially inflated the violent crime rate by around one percent.

The decline in reported violent crime since 2020 has been as widespread as it has been with murders in terms of states seeing declines. The declines haven’t been as sharp, but reported violent crime3 was down in 384 states in 2023 compared to 2020 (about 40 percent of California’ increase is due to one agency's human error mentioned above).

Violent crime is also falling this year in the Real-Time Crime Index, with violent crime down more than 4 percent this year compared to last year through August. Violent crime was down in 2024 compared to 2023 in 23 of the 29 states with more than 900 violent crimes reported through August.

Not every crime is successfully reported to police, which is what makes the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) so useful. NCVS showed a small dip in violent crime in 2023 relative to 2022. Violent crime declined substantially in 2020 and 2021 before rising in 2022 per NCVS. According to BJS, violent crime in 2023 was not statistically different from violent crime in 2019.

NCVS is helpful because it attempts to quantify crimes which are not reported to the police, but NCVS has a few quirks. NCVS is a survey which carries (sometimes sizable) confidence intervals which makes definitively saying “crime X was down Y percent in NCVS” inadvisable. NCVS also doesn’t measure murders which, as I mentioned, is the crime trend that changed the most. Still, NCVS clearly shows the general trend of violent crime in the Unites States over the last few decades.

There’s always some uncertainty as to the exact figures with the nation’s violent crime trends, so I prefer to focus on where BJS and FBI agree when thinking about these trends. Violent crime likely fell a bit in 2023, has fallen a long way since the 1990s, and is roughly at or around where it was before COVID.

Reported violent crime is falling again in 2024 according to the RTCI, the FBI’s (flawed) early quarterly estimates, and other sources like Major Cities Chiefs Association. When it is released next year, the national violent crime rate for 2024 will almost certainly align with the historic lows reported in 2014, 2019 and 2023 with a good chance of being the lowest violent rate recorded since 1970.

Property Crime

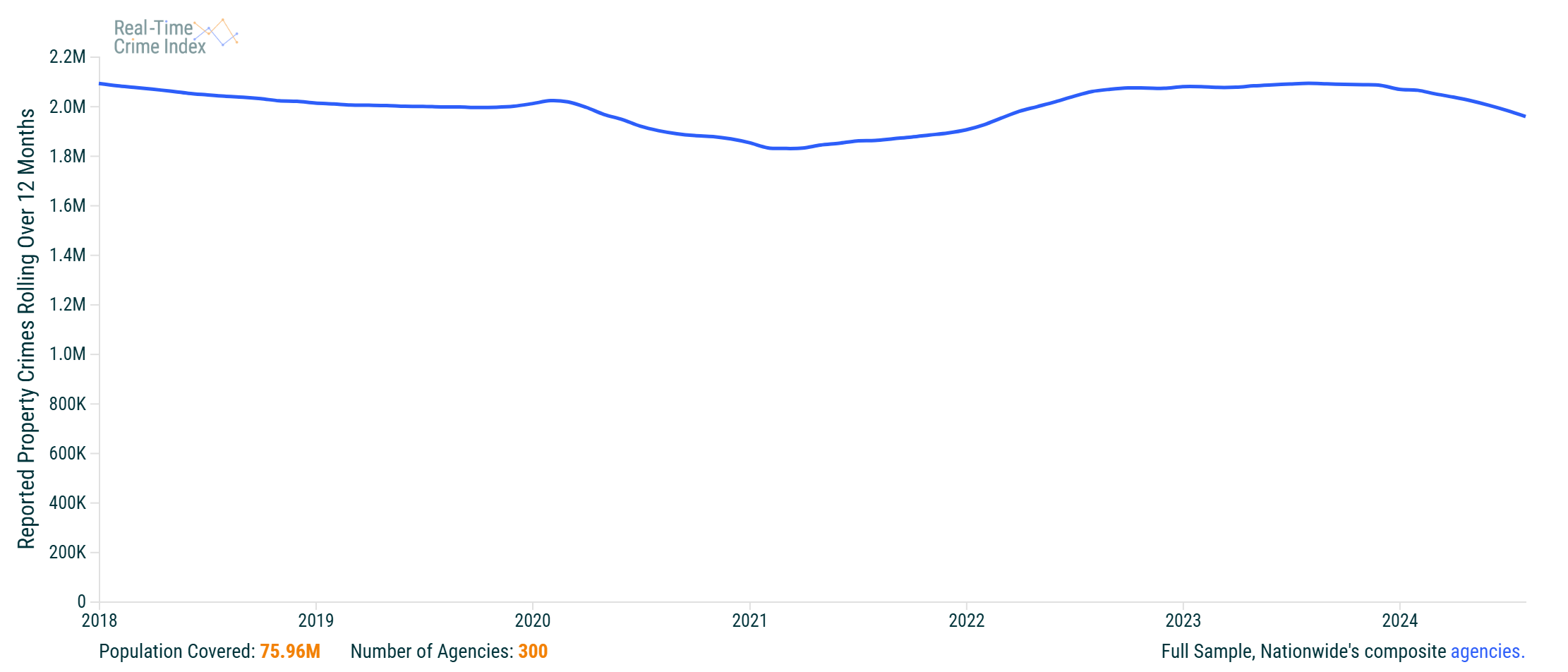

The US reported property crime fell in 2023 to the lowest level since 1962 (again, ignoring 2021’s flawed estimates) in spite of a large increase in motor vehicle thefts.

Data from the Real-Time Crime Index points to property crimes declining even further so far in 2024 thanks to a reversal in the motor vehicle theft increase. Property crime likely dipped during the pandemic (can’t have pickpockets on Bourbon Street if there are no tourists), returned to pre-COVID levels in 2022/2023 driven by increased mobility and the surge in motor vehicle thefts, and is falling again in 2024.

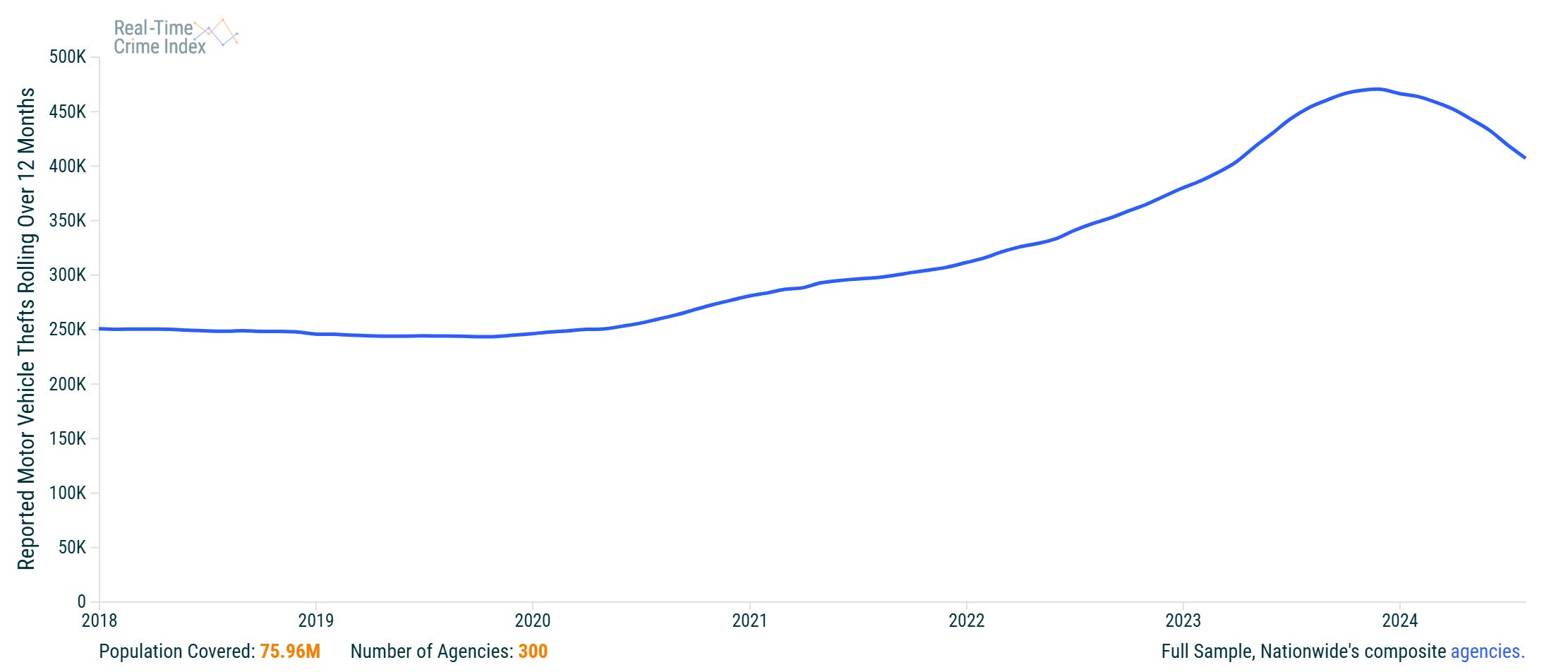

Motor vehicle thefts have risen considerably since 2020 with the increase accelerating in mid-2022 thanks to a video posted on social media showing how to steal certain models of Kias and Hyundais.

The preliminary figures for motor vehicle thefts in 2024 are positive suggesting we’ll see a decline this year. Motor vehicle thefts are down 20 percent through August in the Real-Time Crime Index with more than two-thirds of cities reporting a decline so far this year. Still, motor vehicle thefts remain far more common today than they were in 2018 and 2019 depending on the type of car you drive.

It’s worth noting that property crimes can be challenging to measure because only motor vehicle thefts are reported with any consistency. According to NCVS, around 30 percent of property crimes are reported in a given year. The reported crime trends from the FBI are largely in agreement with the NCVS that property crime was largely even in 2023 compared to 2022 (FBI had it at -2.4 percent, NCVS was virtually unchanged), down substantially since the mid-1990s, and at a relatively steady rate at or near historic lows over the last few years.

Policing

Police staffing data from the FBI points to a decline in officers serving large departments after COVID. This decline persisted into 2023 though it has slowed quite a bit according to the most recent data from the FBI. A majority of agencies with more than 50 officers shrunk between 2019 and 2022 while the share of agencies that shrunk from 2022 to 2023 was smaller for every agency size. Large agencies still lost officers in 2023 though and it remains to be seen what will happen with 2024’s data.

The decline in staffing has had two notable impacts in many of the places that measure it: declining response times and declining traffic stops.

There are no national standards for measuring either response times or traffic stops, but I wrote in January 2023 about how response times were rising in the places that had data that I could find. That piece is a bit dated, but a quick perusal shows the problem continuing.

One place where response times have improved dramatically and that could serve as a model for other cities is — strangely enough — New Orleans. The average response time to all police Calls for Service rose from 43 minutes in November 2019 to over 180 minutes on average in April 2023.

The city took steps to combat this problem and have managed to lower the average response time back to 53 minutes on average in September 2024. They did this in spite of commissioned staffing levels remaining dismal by hiring a lot of civilians to take over tasks that don’t require a commissioned officer and hiring a contractor to respond to non-injury traffic accidents.

The reduction in staffing has led to declining traffic stops in the cities that measure it. The New York Times had a nice writeup on this trend and notes that it is a relatively long term trend. There’s reason to believe that improved staffing — either through more officers or a more efficient deployment of resources — would increase actions like traffic stops. In New Orleans, for example, traffic stops have increased substantially nearly in lockstep with falling response times.

The final major change in policing that I’d like to discuss is the decline in clearance rates (a somewhat flawed approximation of the share of offenses that were solved by arrest or exceptional circumstances in a given year) between 2019 and 2022 followed by a rebound in 2023. The national murder clearance rate, for example, fell from 61 percent in 2019 to 52 percent in 2022 before rising a bit to 58 percent in 2023.

Motor vehicle theft is the only crime type that did not see a rebound in reported clearance rate in 2023. Only 8 percent of motor vehicle thefts were cleared nationally in 2023 which is the lowest share of any crime ever reported cleared. This likely reflects a combination of surging motor vehicle thefts making the clearance rate equation denominator bigger, an already low clearance rate for these offenses, and lower staffing to attack the problem.

Conclusion

The United States should end 2024 with a murder rate that is roughly at or below 2019’s level. The decline coming just a few years after the largest one-year increase ever recorded is a significant achievement that will undoubtedly be studied for years to come.

Violent crime and property crime are tougher to accurately measure due to incomplete reporting, but all indicators point to relatively stable levels at or near historic low rates in both categories in 2023 and evidence of strong declines so far in 2024. These trends are identifiable through a variety of sources which accurately paint a picture of crime in the US. These trends are visible in spite of the frequently discussed flaws in FBI data, not because of them.

US crime trends at present are mostly positive, but there is work to be done. A hypothetical 10 or 15 percent decline in murder in 2024 would mean that there were more than 16,000 murder victims nationwide. And there are cities like Charlotte, Baton Rouge, and Louisville that are seeing rising murder this year in spite of the national trend.

Beyond the major crime trends, there are certainly some issues that are extraordinarily difficult to measure — like retail theft — which may or may not be rising, we just can't accurately tell. There's also general disorder which may not rise to the level of crime, especially major crime as measured by the FBI, but can impact a person's perception of safety.

Other trends such as police staffing and clearance rates appear to be heading towards improvement though that progress could best be described as incomplete at present. Ultimately, one can appreciate the mostly positive current trends while acknowledging that more can be accomplished towards bettering those trends.

Only 56 percent of Pennsylvania’s city populations reported any crime data to the FBI in 2020, the only state in the contiguous US below 70 percent, virtually no rural data was reported, and Philadelphia only reported 4 months. This problem in 2020 was mostly contained within Pennsylvania and Georgia (see below footnote) and large-scale underreporting makes the FBI’s estimates challenging. Coverage in 2023 included 97.2 percent of Pennsylvania’s cities.

Georgia is the only other state with a large number of estimated murders and violent crimes in 2020. I am not using Georgia’s data, however, due to questions in reliability about reporting to the state for that year. The Georgia state UCR program, for example, reports 26 fewer murders in DeKalb County than Atlanta Police Department reported occurred in just Atlanta. As such, I thought it best to leave Georgia out.

Pennsylvania data from the state UCR program again.

Georgia is included in this count based on the FBI’s estimate.

Hi Jeff: A 44 percent increase in violent crime via the National Crime Victimization Survey per you, The Marshall Project and other sources for 2022 is, to my knowledge, the largest increase in violent crime in the nation's history. If BJS is stating that violent crime is essentially unchanged for 2023, the huge increase continues.

Gallup just put out their world study of their measure of fear of crime. It increased in two regions of the world, the US-Canada and Sub-Saharan Africa. It's down throughout the rest of the world.

Reported crime is up considerably in Canada but not in the US "but" Canada requires police participation in collecting crime data and is probably more efficient because of smaller numbers.

I understand a reliance on the small percentage of crimes reported to police in the US and I understand the difficulties of fully participating in the FBI's NIBRS and I understand that police reporting is voluntary.

But for a variety of reasons, the National Crime Victimization Survey was declared over 50 years ago as far superior count of national crimes compared to crimes reported to law enforcement.

Per Gallup and per the NCVS, something just doesn't add up or make sense, especially when considering the multiple flaws of crimes reported to law enforcement. We're the only section of the world (beyond an area of Africa) to record an increase in fear? Reported crime is up in Canada, and Mexico but it's down here?

I don't doubt your data on homicides but that could be nothing more than a reaction to the considerable increases in murder in past years. No crime category stays the same forever.

For those of us trying to understand national crime, the data leads us in multiple directions.

Best, Len.

Do you have a sense of what is going on in Washington state that means its trends are moving opposite the rest of the country so dramatically?