Welcome to the fifth Cautionary Crime Data Tale. The first four parts can be found below:

Enjoy!

I’ve written a few times about how much I dislike Most Dangerous Cities or Safest Cities (or NBA arenas) lists, so it won’t surprise you that I didn’t love a recent piece from MoneyGeek titled “Small Cities and Towns Are Getting Safer, While Violent Crime in Large Cities Is On the Rise”.

This piece starts by raising the question “Seeking respite in America’s smaller cities and towns has its appeal, but how much safer are small towns in reality?” To answer this, “MoneyGeek analyzed crime statistics by quantifying the cost of crime and ranking 1,061 small cities and towns nationwide and in every state.”

To paraphrase Frank Costanza, “I've got a lotta problems with this piece. And now, you're gonna hear about it!”

In order of smallest to biggest nit to pick:

Problem #1 is that the title’s claim of small towns becoming safer while violent crime rises in large cities is not at all addressed. The piece from MoneyGeek is taking a snapshot of 2024 crime data, not a trend yet the title certainly implies that it is evaluating a trend. I’ve done enough freelance writing to not hold a piece’s title against its author though (sorry past editors of mine reading this!), so I can forgive this unfortunate nit.

Problem #2 comes from the implication of complexity in the piece’s methodology. MoneyGeek is using 2023 UCR data using the FBI’s Offenses Known to Law Enforcement by State by City, 2023 table (Table 8). This much is clear because Table 8 weeds out cities that did not report 12 months of data in a given year.

MoneyGeek notes that “Please note that 2023 data was not available for some small cities in Florida. When cities did not have data available in the FBI dataset, MoneyGeek conducted individualized research on standardized crime statistics for each specific city or town.”

What annoys me about that last sentence is that it needlessly implies complexity from a simple process. Conducting “individualized research on standardized crime statistics for each specific city or town” sounds hard! “We downloaded the readily available data from FDLE’s website” sounds less hard.

Problem #3 is that Baltimore is ranked for some reason. Baltimore doesn’t have an NBA team, but that doesn’t quite qualify it as a small town.

Problem #4 comes from MoneyGeek asserting that “The least safe towns are distributed primarily across the South. However, Pine Bluff, Arkansas, of the West, is at the top of the list” (emphasis added). Here is a map of the US with Pine Bluff, Arkansas of the West highlighted. Monroe, LA and Alexandria, LA are both farther west than Pine Bluff and rank fourth and fifth least safe by their methodology yet neither city is considered “of the West.”

Problem #5 has to do with the data itself likely containing errors. According to MoneyGeek, “The safest small city in the U.S. is Columbus, located in Indiana’s Bartholomew County, located roughly 40 miles south of Indianapolis.” Columbus is followed by Wallingford, Connecticut and Wallkill Town, New York is 8th safest.

Yet a closer examination suggests all three cities have data reporting issues, rather than any level of actual crime, as the primary culprit of low reporting. This can be seen by graphing monthly UCR Part I crimes reported by each of those three cities from 2016 to 2023 which I grabbed from Jacob Kaplan’s essential website.

Columbus, Indiana went from 100+ Part I crimes per month before NIBRS to single digits since and Wallkill Town is reporting roughly 50 percent fewer Part I crimes per month after switching to NIBRS. Wallingford’s decline isn’t quite as obvious, but there’s still a sharp drop starting in 2019 and continuing through 2023. It’s not clear what’s causing Wallingford to report fewer incidents, but the graph of theft, burglary, and aggravated assaults in Wallingford rolling over time raises the suspicion level that reporting practices have changed.

American crime data reporting is flawed and has always been flawed. People should take special care not to mix up the most flawed reporting cities with the safest cities.

Problem 6 is actually three problems revolving around the methodology used to calculate “safest” in the first place. The methodology implies certainty, but crime counts are inherently uncertain given how much goes underreported.

MoneyGeek’s methodology amplifies this problem by implying certainty about the cost of each crime type using a very, very uncertain process. To calculate the cost of crime, MoneyGeek took a study from 2008 which estimated what each crime costs society in 2008 dollars and then adjusted for inflation (multiply by 1.4152). Here’s how you get $40 per capita (population of 43,902) of crime in Wallingford, CT:

There are at least three main issues with this methodology:

Problem 6a: Crime is underreported. Less than a quarter of rapes/sexual assaults tend to be reported to police according to the National Crime Victimization Survey yet rapes are considered to have the second highest cost to society by quite a large margin. The “safest” cities, therefore, may just be the cities that do the worst job tracking sexual assaults.

Problem 6b: Crime isn’t always reported in the year it occurs which is problematic given how much weight a single murder carries in measuring “safety” in this methodology. If a person is shot in 1990 but dies in 2023 then they’re counted as a 2023 murder for “safety” purposes. A single murder reported in Wallingford in 2023 would have pushed the city from second “safest” all the way down to 215th despite a single murder not really changing the actual level of safety in the city. Greenwood, SC — where murder was almost comically overreported — would have been considered nearly four times less safe in 2022 than Pine Bluff was in 2023 ($40,000 cost of crime per capita vs $13,000).

Problem 6C: MoneyGeek discusses the “Cost of Crime” as though it is a concrete figure rather than a guesstimate. The 2008 study used by MoneyGeek shows a diversity of findings around the cost of each crime type between various studies which could have dramatic impacts on the cost of crime per capita in each city. It’s also not immediately clear why household burglary is used and whether other types of burglary (i.e. commercial) are included in those costs.

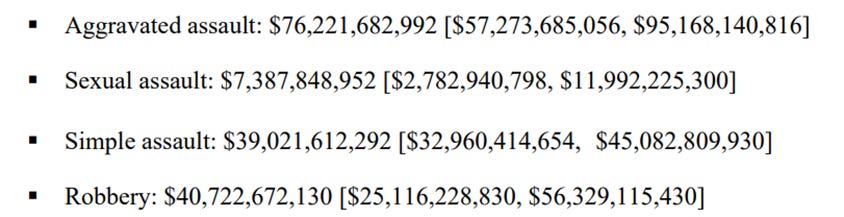

Other studies, such as this 2023 study from NORC shows substantially different costs to victims with (very appropriately) margins of error to convey the vast uncertainty in these measures:

It is absolutely fair to try and measure the cost of crime in a city, but these measurements are just best guesses and should be treated as such. Ranking cities based on cost of crime compounds uncertainty of reporting with uncertainty of cost to create a largely nonsensical ranking.

There is, however, an easy trick that interested authors can do when trying to create a safest/most dangerous list: don’t do it! These methodologies are always flawed in ways that tell the reader nothing real. The FBI has cautioned against rankings like this for a long time, writing in 1995:

Each year when Crime in the United States is published, many entities—news media, tourism agencies, and other groups with an interest in crime in our Nation—compile rankings of cities and counties based on their Crime Index figures. These simplistic and/or incomplete analyses often create misleading perceptions which adversely affect cities and counties, along with their residents.

Not every city reports data every year, those that do report data don’t always report complete data, and no agency fully accounts for unreported crime. The urge to compare how your city stacks up against similarly sized cities is real and it is constant (I know I’ve done it too!), but the best solution is to avoid doing so whenever possible. If you’re going to rank, then you should acknowledge the flaws of using reported crime data and appreciate that those flaws add a good bit of uncertainty to your ranking methodology.

Thx Jeff. A voice in the wilderness, I fear. For some reason that I can't wrap my remaining brain cell around, Americans (people in general?) insist on being afraid of "crime", whether it exists or not. Be afraid, be very afraid.

"If you want to control someone, all you have to do is to make them feel afraid.”

- Paulo Coelho, The Devil and Miss Prym

This tendency to create pointless, but worrying rankings is just standard, lazy, journalism. We need to stop viewing media as informative - they ARE entertainment... Selling eyeballs to advertisers.