National Crime Data Has Always Been Flawed

None of these problems are new.

Our national crime statistics under the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR) are flawed, have always been flawed, and will almost certainly be flawed well into the future. UCR collects data voluntarily submitted by agencies requiring estimation to approximate US crime counts and trends when reporting is inevitably incomplete. But the flaws in UCR does not prohibit us from understanding national crime trends, and new technologies are making it possible to see those trends faster than ever before.

Stepping back and taking a look at the entire history of national crime statistics in the United States shows that the uncertainty about our crime stats now is not unique. And that constant uncertainty does not obviate our ability to understand crime trends historically or today.

We can more or less divide the history of UCR into 6 very unofficial eras Viewing the history of national crime reporting in this manner helps to explain the constant imprecision of our national crime estimates.

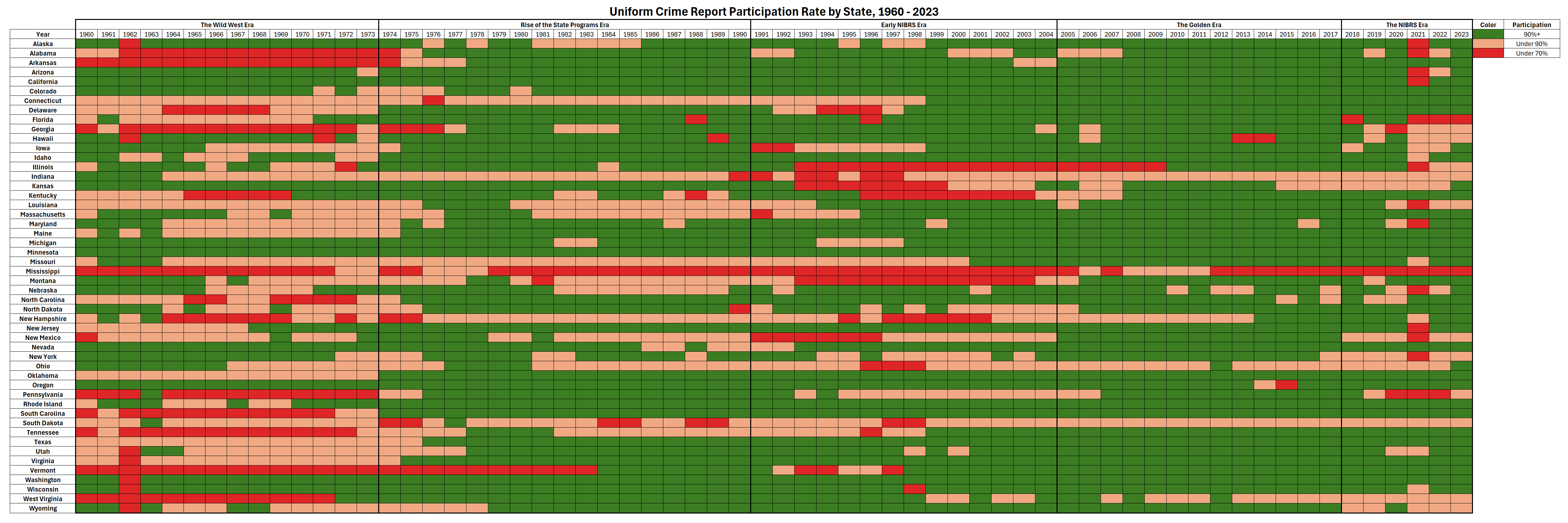

A good way of dividing up these eras is by evaluating the share of the population that reported data each year. More reporting equals more accurate national crime estimates, but it’s not always obvious exactly how much of the population reported data in a given year because agencies will occasionally report only partial data.

One can use participation data to do this, but not every agency that participates in UCR in a given year sends in crime data, and sometimes an agency won’t send in a full year of data. A different way of measuring the share of the population reporting each year comes courtesy of a trick I stole from Michael Maltz to account for agencies that only partially reported crime data. Using this technique, if a city only reports 6 months of data in a year then it only gets credit for half of its population as having reported.

Using this method produces the below graph which neatly maps out the eras since 1960 (notes: UCR data goes back to 1930, but monthly counts are only reliably available starting in 1960. Additionally, 2023’s data is the only year that has not been revised because it was just released. I would imagine it will show a decline from 2022 once revised next year). This graph fits relatively neatly into the 6 separate eras of national crime data that I’ve identified1.

Viewing reporting in this manner accounts for when agencies participated in UCR but didn’t send full crime data. It also highlights just how normal it is for the FBI to have to estimate 5 to 10 percent of the US population’s offenses. And, finally, it highlights just how unknowable 2021's crime counts *still* are because of the NIBRS transition.

Era 1: The Wild West (1928 - 1973)

The idea for national crime statistics originally came about shortly after the end of the Civil War, but it wasn’t until 1930 that the Uniform Crime Report was first launched. UCR was conceived as a voluntary program with a goal of collecting standardized crime data from across the country. One of the main motivations behind UCR was in response to false narratives of “crime waves” with a piece in the FBI’s Law Enforcement Bulletin in 1938 noting that “in some communities (the UCR) may even furnish the statistical standards which can be effectively used by the Chief of Police to refute the existence of those imaginary "crime waves" which are sometimes foisted upon a department by political backbiters.”

The first Uniform Crime Report was published in 1930 and data was has been released monthly, quarterly, semiannually, and annually at various times. The share of the US population covered began rising in the 1950s with about 75 percent covered in 1955 and nearly 95 percent by the end of that decade (with 89 percent of the population represented by complete data).

Still, data was submitted directly by agencies with little available means to determine its accuracy. It’s also not fully clear what share of the population was represented given that population estimates in the 1950s relied on the 1950 Census until 1959 when they used “preliminary figures from the 1960 count”.

The FBI caveated its early reporting in ways that acknowledged just how inaccurate these totals may be. As late as 1957 the UCR carried a caveat that: “in publishing the data sent in by chiefs of police in different cities, the FBI does not vouch for their accuracy. They are given out as current information which may throw some light on problems of crime and criminal-law enforcement.” And in 1959 the FBI caveated its data by noting “In publishing these figures, the FBI acts as a service agency. The figures published are those submitted by the contributing agencies. The FBI, through its verification procedures and personal contact program, attempts to hold to a minimum the instances where a community's crime figures fall short of full compliance.”

That's some serious CYA!

The Crime in the United States publication began looking like the more modern version around 1960, and most measures of national estimates begin then thanks annual and monthly data from that year being easier to access electronically. But there are still lots of holes.

The count for many states from 1962 is tough to recreate because much of that year's data is presumed to have existed but is missing. Per Maltz — I kid you not — the data is missing “for part of Texas and all of Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, Alaska, and Hawaii. When I contacted the FBI about this omission, I was informed that they had inadvertently overwritten one of the 1962 magnetic tapes on which their data was stored, apparently the last tape for that year.”

The lack of a centralized reporting process raises questions as to the precision of these early figures — which is a kind way of saying that the FBI’s estimates prior to the 1970s should be taken with an enormous grain of salt.

Era 2: Rise of the State Programs (1974 - 1989)

In 1967, the FBI began encouraging states to spearhead the collection of data rather than having agencies send data straight to the FBI. Two states were doing this by 1969 (California and New Jersey), 22 states by 1974, and more than 40 states by 1980. The growth in state UCR programs has been helpfully charted by Maltz in the below graph:

Standardization of these procedures led to improved reporting and almost certainly better accuracy in the national estimates. Notably, clearance rates began plunging in the late 1960s possibly due to better reporting standards being applied by state programs (my guess — subject for another time perhaps).

Reporting issues with Illinois began popping up in 1986 and Florida and Kentucky both had challenges in 1988 leading to no data being reported from either state those years, but overall reporting was far improved in these years. NIBRS was first implemented in 1989 leading to…

Era 3: Early NIBRS Era (1990 - 2004)

Many states began to transition to NIBRS well before the FBI mandated it in 2021. This created issues within many states causing a drop in participation through the mid 1990s before seeing improvement in the late 90s and early 2000s. These single-state issues were typically short-lived and didn’t come all at once which helped limit the damage.

Illinois continued to have data reporting issues with the problem worsening in 1993 due to “NIBRS conversion efforts” which remained problematic until Obama’s first term. Other states had more intermittent issues — some related to NIBRS, some not, which you can read more about here.

There are plenty of examples of individual agencies that had reporting issues over this span. Take the very suspicious case of motor vehicle thefts in Fairfax County, Virginia. Fairfax averaged 160 motor vehicle thefts per month pretty consistently from 1990 through 1998, but the agency failed to report any data (for any crime) in 1999. The agency reported just 30 motor vehicle thefts per month when reporting resumed in 2000 and in 2001 before increasing to 111 per month between 2002 and 2005.

Two major changes occurred during this era that created added importance and awareness of crime data. First, data became accessible via the internet. The Uniform Crime Report was available in paper format prior to 1995, but the 1995 version is the first version that is available digitally.

Second, Maltz notes that “the fact that the UCR data have, for the first time, been used to allocate Federal funds brings issues about data quality to center stage.” The use of UCR statistics to allocate Federal funds should, in theory, provide a large incentive for agencies and states to get their data right. That isn’t always the case though, even today.

Crime was substantially higher in the US in the 1990s than it is today despite the substantially lower participation rate those years. This provides a good example of how the nation’s crime trends can be crystal clear even if the reporting adds uncertainty as to the precision of the numbers.

Era 4: The Golden Era (2005 - 2017)

By this time, states had solved their problems from the 1990s and the states that were motivated to switch to NIBRS had done so. Only one state (Mississippi) had less than 80 percent participation in 2010 as participation in the Uniform Crime Report reached new highs.

As such, the estimates from the early 2010s are probably the most accurate on record. But there are flaws in reporting even in the “Golden Era” meaning even the best years of reporting was not inherently precise.

There are plenty of examples of shoddy reporting that makes national crime estimates imprecise, even under the best of circumstances.

A 2006 study of UCR data in West Virginia found 4 percent of offenses contained classification errors (i.e. an aggravated assault recorded incorrectly as a simple assault). Other agencies either didn’t report or underreported certain offenses. Tucson (AZ) failed to report any theft data for the years 2006 to 2012, investigations in New Orleans found the department systemically underreporting rape in multiple years, and the South Bend Police Department received new guidance from the FBI in 2016 which led to a substantially higher share of assaults being marked as aggravated rather than simple assaults.

In December 2015 the FBI announced plans to move to NIBRS and retire the Summary Reporting System by the end of 2020. Some states and agencies began making plans for life under NIBRS, but overall participation in NIBRS remained low. The share of the US population covered by a NIBRS-compliant agency only increased from 24 percent in 2004 to just over 30 percent in 2017.

Era 5: The NIBRS Era (2018 - 2023)

Participation in NIBRS surged as the 2021 deadline approached, with 36 percent of the population covered in 2018, 45 percent in 2019, 54 percent in 2020, and 65 percent in 2021 (see CDE for those spreadsheets). Still, that total was far less than what normally gets reporting leading to an essentially lost year for national crime estimates in 2021.

The share of population reporting data jumped in 2022 and 2023 as states embraced NIBRS though the jump was to largely the same level as the early 2000s. The FBI’s decision to allow agencies to submit data via SRS and revisions to recent years has greatly improved the share of agencies nationwide reporting crime data over the last few years.

The NIBRS transition was most seriously felt in 2021 where nearly 40 percent of the population failed to initially report including more than 20 states with less than 80 percent population coverage. The FBI allowed states to submit non-NIBRS data in 2022 which substantially improved coverage.

Still, it’s hard to estimate national crime counts with minimal data from California, New York, and Florida. Fortunately, the 2022 estimates were far better than the unusable 2021 estimates, and the evidence suggests that 2023 should be better than the 2022 estimates.

Conclusion

NIBRS participations is rising and with it comes better access to more crime data faster than ever before. Missingness may be improving nationwide but there are still issues of incorrectness as evidenced by one agency inadvertently reporting nearly 10,000 more violent crimes than were recorded.

Hopefully this piece has driven home just how usual it is to have incomplete data in our national crime estimates — that’s why they’re estimates. We have no idea just how accurate the estimates from the 1960s and early 1970s are, and the estimates from the 1990s and early 2000s suffered from similar issues though not quite to the same degree).

Some states, like Mississippi and Illinois have had long stretches with consistent underreporting. Other states such as Minnesota and Washington have been star pupils since the start.

Recent estimates are about as good as they’ve ever been (2021 excepted), but that doesn’t mean they are precise. We already know that most crime types are underreported to the police, so people should be inherently aware that these figures are not 100 percent correct.

The best solution to the problem of imprecision is to speak about crime trends in a general sense wherever possible.

The difference between an estimated 2 percent decline and an estimated 4 percent decline is not much, and both speak to a gradual decline from one year to the next. One can speak of reported figures with precision (“the nation’s murder rate in 2023 was estimated to be 16 percent lower than 2020’s rate but 9 percent higher than 2019’s”), but speaking of trends less specifically helps to account for some of the uncertainty inherent in the estimates.

One should also use multiple sources for understanding overall crime trends. Our Real-Time Crime Index was built for this purpose, but you can also use NORC’s Live Tracker, the Council on Criminal Justice's regular reporting, the CDC, the Gun Violence Archive, and more to confirm the contours being reported in the FBI data.

Crime data is flawed and those flaws are clearly seen in the FBI’s annual report each year. This is not a new phenomenon, but one should not let perfect be the enemy of good enough when trying to accurately discern nationwide crime trends.

Remember that these eras a fuzzily defined, and reliable participation data starts in 1960 which is why the graph starts then.

Do the issues with national crime data call into question any of our narratives around the rapid increase in violent crime in the 1960s into the 70s? That narrative feels pretty indisputable, but I'm curious how we account for the increase in reporting/flaws in data with what we know about rates of violent crime in that era.

I was a cop from 92 to 94 in a very small (college) agency. We were early adopters of NIBRS, but still had to report under UCR. It was interesting to see how the sausage was made, as it were.

Is there a solution to poor reporting? Can/should it be mandated, with penalties for failure?