The Real-Time Crime Index Is Live!

Version 1.0 is here!

The Real-Time Crime Index (or RTCI for short) launches today at https://www.realtimecrimeindex.com! The RTCI presents a new way of looking at crime data by collecting current crime data from hundreds of law enforcement agencies nationwide to present national crime trends as never seen before: as they develop.

You remember the awe you felt when scientists released the first photograph of a black hole? Well seeing preliminary crime trends as they develop across a wide sample of cities should inspire the same feeling (ever so slight hyperbole alert). This is what the national murder trend rolling over 12 months looks like:

They say that a picture is worth 1,000 words, well this picture is truly worth 1,000 words describing how murder has progressed over the last 5 years in a far more digestible format than relying on YTD and year on year percent changes.

The RTCI was built thanks to generous support from Arnold Ventures and incredible hard work from the RTCI team: Dave Hatten, Katie Schwipps, and Oscar Boochever (as well as my co-founder Ben Horwitz and a ton of people who helped advise on data collection, auditing, and visualization). The goal of this project is to provide this information so that anyone — regardless of their location, expertise in crime data, political persuasion, or policy preferences — can use it to understand crime locally or nationally.

The RTCI currently has data from more than 350 agencies covering over 80 million people though not all of those agencies have available data for every month from January 2017 through June 2024. The agencies that do have data for every month since 2017 make up the nationwide sample which as of June 2024 has 304 agencies covering over 76 million people with full data in at least one crime category. The national sample right now covers around 25 percent of the nation’s population and 45 percent of the murders that occur each year.

I’ll do a post tomorrow with much more detail about what the RTCI says about national crime trends and another post — probably next week — going deeper into the methodology behind the RTCI. Overall, violent crime and property crime are falling in the United States according to the RTCI’s sample of data through June 2024. Murder was down roughly 16 percent midway through the year, with overall violent and property crime down 5 and 9 percent respectively. The RTCI also shows that the big property crime decline is being driven by motor vehicle theft falling 17 percent, after rising considerably each year from 2020 through 2023.

But the beauty of the RTCI is that anyone can see the data, the trends, the sourcing, and the methodology to evaluate what’s happening. All of the current data for every city comes from either agencies themselves or state UCR programs with data received either through publicly available open data or sent to us directly from agencies or state UCR programs.

You can sort through all the agencies and view data by month or rolling over 12 months (as shown above) The latter option shows the total number of offenses over the most recent 12 months of reported data to get a smoother view of the overall trend, so data for June 2024 contains all crimes committed between July 2023 and June 2024. This is especially important for evaluating changing trends while accounting for seasonal impacts on crime. You can compare YTD counts across agencies or drill down on crime counts over time in an agency and see what real events did to crime rates such as a big jump in burglaries reported in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida in 2021.

Or the wild surge in auto thefts (and subsequent fall) in Philadelphia following a video showing how to steal certain models of cars being posted on TikTok.

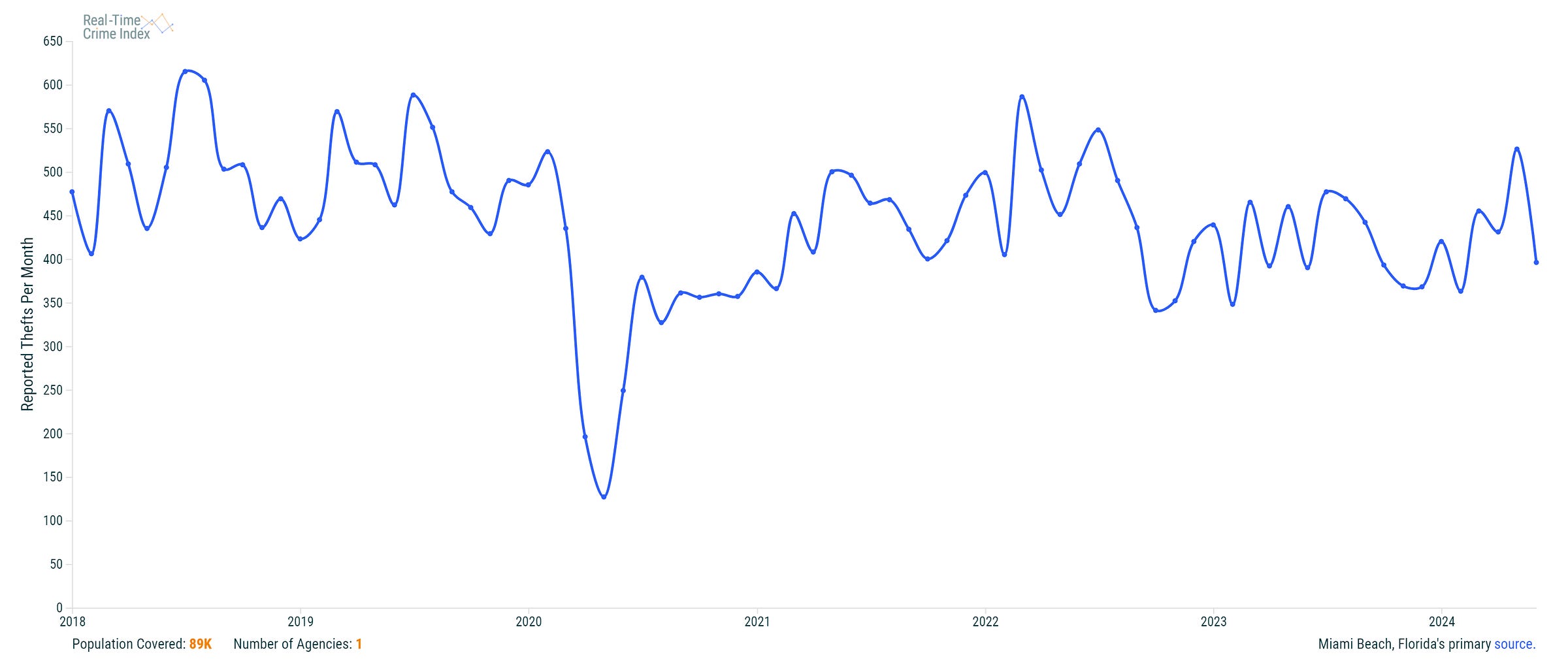

Or the impact of COVID shutdowns on thefts in Miami Beach:

The data has been standardized to match FBI Uniform Crime Report Part I offense types. It’s worth noting that not every agency reports every crime type and not every agency adheres directly to the UCR Part I definitions in their publicly available data. New York, for example, publishes monthly counts of felony assaults and grand thefts while Washington, DC publishes data on “Assault w/a Dangerous Weapon” rather than aggravated assault. These won’t match exactly what is reported to the FBI but the trends should match very closely. Some agencies also don't report rape counts in their public data, so those agencies will show up as having no rape data.

Viewing crime rolling over 12 months is a far superior means of evaluating trends compared to using strictly Year-to-Date, and this is the advantage of standardizing agencies and timeframes to be able to build a national sample of several hundred agencies. YTD calculations can be very useful, especially late in a year, and I built a YTD dashboard to track changing murder nationally so I totally understand its particular purpose, especially in the absence of more granular data.

But much of the usefulness of using YTD to assess crime trends comes from a lack of other, better, ways to assess things. Rolling crime over 12 months accounts for possible weather effects and helps you to understand if crime is up or down relative to what’s normal or if the YTD change you’re seeing is because last year was particularly bad. If you want to understand a trend in context or see whether an event or policy has had an impact then rolling over time is the way to go in this analyst's humble opinion.

I could continue, but I’ve previously written on the plusses and minuses of using YTD and Jerry Ratcliffe wrote a fantastic piece on YTD a few years ago that remains must read, so check those out!.

A 12 month rolling average also helps to alleviate the possibility of underreporting of crime in more recent months which gets corrected as the year goes on while also accounting for potential seasonal effects on crime. This is further alleviated by having data from hundreds of agencies, the vast majority of which are fully (or nearly fully) reported with a month and a half lag.

The result is a dataset that is standardized by offense definitions and timeframes to create a novel picture of local and national crime trends. I don’t think that we are significantly understating current crime figures due to substantial underreporting of more recent months, but it’s always possible that this is playing some role. Having a bit of a lag to allow agencies to catch up and auditing each agency enables outliers that would bias the sample to be caught and removed.

The RTCI is meant to compliment — and in no way replace — the national estimates being produced by the FBI. There is value in having data fast that shows the trends and there's data in having data slower that provides strong national estimates. The RTCI, taken with other sources such as the CDC, the Gun Violence Archive, the FBI's quarterly reports, or NORC's Live Crime Tracker (amongst others) help build a comprehensive picture of crime trends as never known before.

Like every tool involving crime data, there are caveats that users should be aware of when using the RTCI.

First and foremost, this is a sample rather than a full collection of national data. National crime trends tend to closely follow a sample of this size, but we can’t say for certain just how closely the sample and national trends will align. The RTCI saying murder is down 16 percent in the sample through June does not mean that is where the figure will end up in December and it doesn’t mean that murder is down exactly 16 percent nationally right now.

The data is preliminary and some agencies will update data from recent months in the future, so these numbers will change slightly as time goes on. We are using a roughly month and a half lag to account as best we can for this problem — an agency’s June data is nearly fully complete when it reports its July data in early August — but there’s still going to be small changes for some agencies that will be reflected in the data later on down the line.

Crime data is imperfect and the RTCI attempts to account for that imperfection as best as possible. We are doing our best to identify where underreporting might be occurring and dig those agencies out of the national sample. Doing this prevents the more recent months from persistently showing a large decline in crime.

Additionally, the figures reported on the RTCI may not exactly match what is reported publicly for some agencies based on the methodology used to gather data. The important part is not obtaining exactitude from an inherently inexact dataset, but rather to accurately identify trends at a local and national level as they develop.

Oh, and RTCI is made up of reported crimes. We know that some crime types are systemically underreported to police, but we can't build a collection of incidents that weren't reported.

The plan going forward is to update data in the middle of each month covering the month before the most recent completed month. So in about two weeks or so we will update the data to cover July, the update in October will cover August, and so on.

The RTCI is going to evolve, so the version you’re seeing now — version 1.0 — will change and grow (hopefully for the better). If you have suggestions or identify necessary fixes please let us know! We hope to add agencies and add different data types to improve the usefulness of the RTCI as time goes on. And if you represent an agency or know of a data source that should be added, please let us know!

For updates on the RTCI you can join our mailing list for information on developments, trends, and webinars and other events.

Wonderful resource, Jeff--this is a hugely valuable effort! One thing I am curious about is how you will handle situations where an agency that is currently reporting data today stops reporting data in the future, or you want to add a new agency. For people who stop reporting, if you completely take an agency out, then that has the effect of making past values from today's RTCI different from previous editions of the RTCI, which doesn't seem ideal. If you don't take it out, then you can get "increases" or "decreases" in crime that simply reflect compositional changes, which is definitely bad. And for newly reporting agencies, are you going to require that an agency produces numbers all the way back to the earliest point in the index before it can be included? That avoids to compositional issues but may limit your ability to bring new agencies online, as many jurisdictions who launch new real-time reporting systems might not include data far back into the past.

I think this is a situation where you might consider not actually including all available agencies but instead doing a weighted average of some subset of agencies (one obvious approach would be to choose the weights to match the trajectory of actual realized national numbers in earlier years), like they do with the Dow Jones Industrial Average or S&P 500.

As a data visualization nut, I’m obsessed!!! How do I volunteer? Absolutely great work!