How Early Is Too Early For YTD Crime Stats?

Figuring out when Year-To-Date is predictive of overall trends.

I was on Jerry Ratcliffe’s Reducing Crime podcast last year and we had a great conversation on a variety of topics related to law enforcement data (interrupted by me checking my phone and seeing the Saints had blown a late lead to the Bengals).1 The lively conversation turned to the use of year-to-date (YTD) data to evaluate crime trends and Jerry very memorably turns to me and says “oh, I have thoughts on year-to-date” with the scowl of a man who was discussing his mortal enemy.

Indeed, Jerry does not like YTD and has written a very good piece that is worth an annual read about their shortcomings. Jerry and I agree about both YTD’s shortcomings as well as a preference to use measures like a rolling count or average for more accurately evaluating crime trends.

Consider New Orleans where saying shooting incidents are down slightly YTD in 2023 does not begin to tell the story of gun violence being persistently much higher when viewed rolling over 365 days.

Jerry is especially right about YTD totals early in the year being particularly useless. He writes “The bottom line is that with crimes such as homicide, we need not necessarily worry about crime panics at the beginning of the year. This isn't to say we should ever get complacent and of course every homicide is one too many; however the likely trend will only become clear by the autumn.”

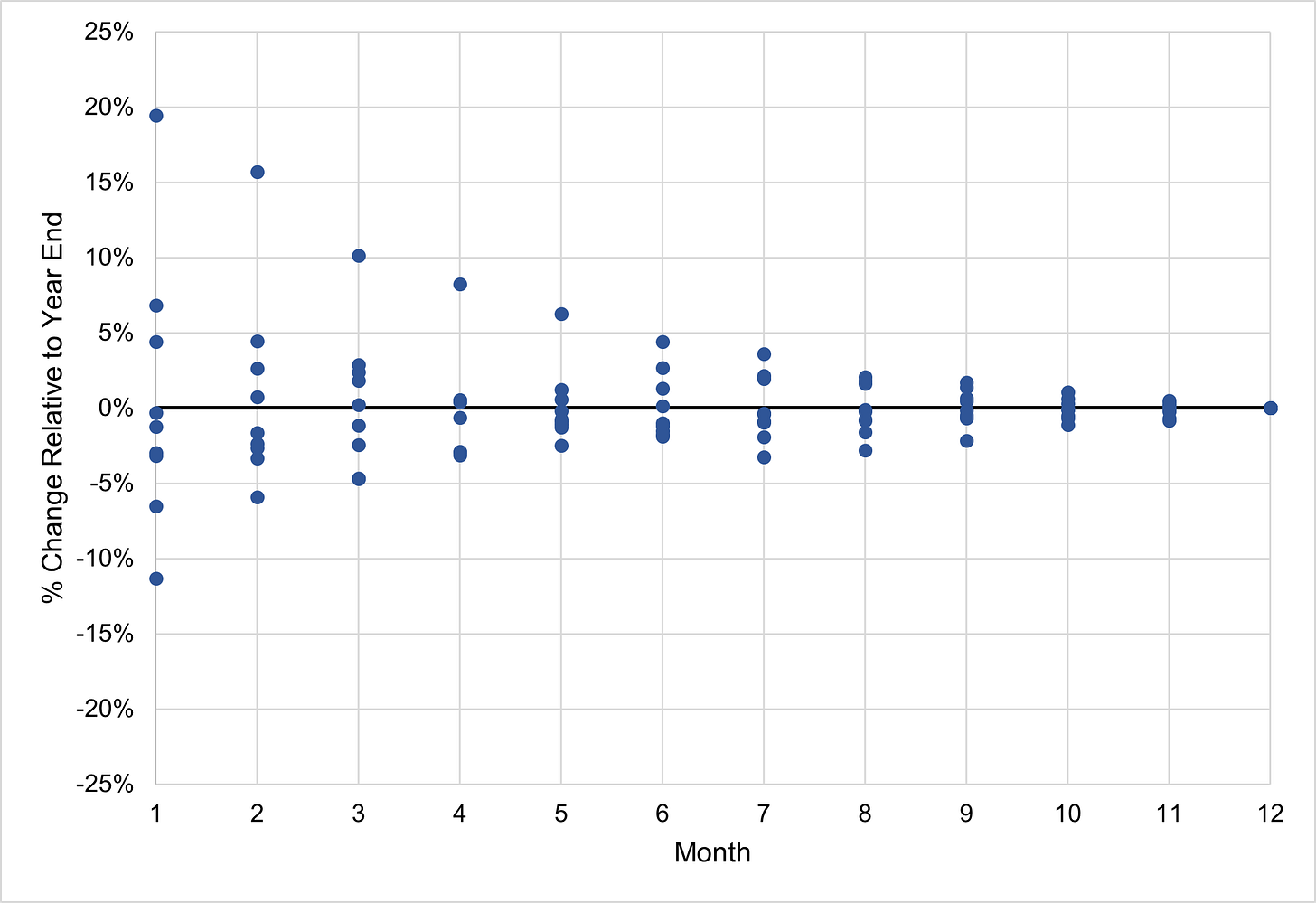

There is a nice graph in Jerry’s piece showing how off the change in murder in Philadelphia is each month early in the year relative to the year-on-year percent change recorded in December. The FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Report data provides an excellent source for highlighting this trend in other cities.

Below are two graphs showing how the percent change in murder through each month of the year compared to the year end change between 2016 and 2019. In New York City, for example, the YTD percent change in murder rarely got close to the year end percent change until August or September — that is to say that if murder was up 30 percent YTD through January but ended the year up 2 percent then it was off by 28 percent through January.

Indeed, having data through March for NYC was practically useless for figuring out the city’s murder trend between 2016 and 2019. It was not truly reliable — say within 5 percent of the year end change — until October or November. The city’s YTD murder percent change through June was just as likely to be 10 percent higher than the final percent change as it was to be 10 percent lower.

The same is true for Houston shown below where the city’s murder trend could not really be known over those years until November.

I did not include 2020 — the year’s weirdness caused massive unique changes — or 2021 — the NIBRS transition produced substantially less data — but these examples should serve as a warning not to rely on YTD for an individual city until you’re in a month that ends in ‘R’.

The issue becomes substantially less pronounced — and perhaps where Jerry and I might disagree — if you have a lot of cities of data. To show this I took SHR for every city that reported between 2010 and 2019. The margins are MUCH smaller, and if we had thousands of agencies reporting data regularly then we might have a very strong idea of the country’s murder trend by May or June.

Alas, we do not have several thousand agencies regularly reporting YTD crime data in a public format. The workaround has been to gather publicly available data for as many big cities as possible which we at AH Datalytics show in our YTD murder dashboard. We usually get data from between 75 and 95 agencies including many of the country’s largest and update the data weekly.

It turns out that 75 cities does a pretty good — albeit very imperfect — job of predicting the national trend by midyear. Below is the same graph but with only monthly data for the 75 agencies that reported the most murders from 2010 to 2019. The Y-Axis compares how predictive data from those cities was compared to the national change in data reported at the end of the year.

Between 2010 and 2019, if you had 75 big agencies worth of murder data in July then on average you would be within roughly 2.5 percent of the national year end change. It isn’t perfect and I would love to be able to build a real-time count of murders rolling over 12 months across a host of cities, but that data is not available. So YTD is the best we can do given the sad state of the US national crime reporting system.

So if it is June and murder is down 6 percent in our sample of 80 or so big cities then that is a pretty good indicator that murder is declining nationally. Moreover, big cities tend to overstate the national trend, meaning that murder is down more in big cities relative to the national change when murder is declining nationally and vice versa when murder is increasing nationally. If murder is down 8 percent through September in the big city sample then that suggests a roughly 4 to 6 percent decline nationally may be occurring.

We will start updating the YTD murder dashboard soon, but one should not read too much into the data just yet. Last year our March update shows murder up 4 percent in cities with available data which turned into -5 percent by December. Give it until the summer before you really start to believe whether murder is going up or down nationally.

At a city level, you can start to buy into the trend in July and August. But if you really want to know when YTD is a reasonably reliable predictor of the national trend then you should follow Green Day’s advice and ”wake me up when September ends.”

It was a great conversation and you should definitely give it a listen.

I'd love to know the following, which I think might help the issue:

1) What is the r^2 of YTD data each month predicting final YTD data (the aggregate not city by city)?

2) What is the r^2 of each month at predicting final YoY changes? I.e. if murders are down in June 2022 vs June 2021 is that more predictive compared to murders down in August 2022 alone vs. August 2021 alone? The volume of murders is obviously higher in the summer so I am wondering is are we just gaining by getting closer to the end of the year and that's the cause of the predictive gain or are we gaining because early in the year the volume is lower and so just not as informative.