How Many Violent Crimes Were Reported Nationally in 1967?

The problem with exact national crime figures.

The St. Louis Cardinals won exactly 101 games in the regular season in 1967 before beating the Boston Red Sox 4 games to 3 in the World Series. The Green Bay Packers went exactly 9-4-1 before winning the Super Bowl in 1968 while my beloved New Orleans Saints kicked off as a franchise by going 3-11 (though one of those wins came against the hated Atlanta Falcons).

I was able to look up those facts about an ancient era in just a few seconds on the internet. But what if I want to look up how many UCR Part I violent crimes were estimated by the FBI to have occurred in 1967?

Seems easy enough, the FBI began reporting national crime estimates in 1960 which surely means the 1967 estimate should be simple enough to find, right?

The first step in the journey for crime data is usually to check out the Crime Data Explorer (CDE). CDE has two ways of potentially getting at those figures. First, there’s the crime data query tool that was recently added that lets you pull crime figures from an agency, state, or nationally. Unfortunately, this tool only goes back to 1986 so it won’t be much use going back to 1967.

The other possible way would be to download the Summary Reporting System spreadsheet that’s in the Additional Datasets portion of the downloads page. This has data by state and nationally as well, but it sadly only goes back to 1979, so no dice.

Prior to CDE, the FBI maintained a website called UCRDataTool.gov which provided agency, statewide, and national data from 1960 to 2014. That website ain’t there no more but you can see it’s reasonably simple and useful interface on the Wayback Machine. The FBI also has old Crime in the US reports online, but those only go back to 1995. There's a table in there that goes back 20 years, but that still just gets us to the mid-1970s.

With all other options expended, that leaves using individual scanned PDFs of the original Crime in the US reports published by the FBI as the only way to figure out how many violent crimes there were in 1967. These can be found on Archive.org, but you have to know where to find the correct table within them to use them properly.

The 1967 Uniform Crime Report can be found here, and if you turn to page 60 you see Table 1 which gives the numbers of murders, rapes, robberies, and aggravated assaults in 1967 as 494,563. With a US population of 197,864,000 that’s good for a rate of around 249.95 violent crimes per 100,000.

In Table 2 of that document you’ll notice that they’ve rounded the violent crime figure up to 494,600 which is probably a good idea at all times given the uncertainty of crime estimates at a statewide or national level, so let’s use that figure as our number of violent crimes in 1967.

That answers the question — there were 494,600 violent crimes in the US in 1967, right?

Table 2 back then showed current year as well as recent previous year crime counts, and while the Table 2 from 1970 still shows 494,600 violent crimes in 1967, the table in 1971 and 1972 puts it at 495,740. The number of violent crimes in 1967 then rises up to 496,150 in 1973, 497,290 in 1974, and 499,930 in 1975.

The US violent crime rate for 1967 rose from 249.95 when first published to 253.18 in 1975 with no clear explanation why. Were that many agencies really updating crime figures from 1967 in 1975 to add over five thousand violent crimes to the national total? Seems unlikely.

When preparing a chart of the US violent crime rate over time, which rate should one use?

This mystery isn’t a trivial, historical, or academic matter either. When the FBI published its Crime in the US report for 2022 for example, the US violent crime rate for 2003 was revised up from 475.8 per 100,000 to 501.8 in the table of crime rates in the US over the last 20 years. There were also smaller revisions to more recent years like 2019 (which was at 366.7 in 2019, was revised up to 368.9 in 2020, and then was revised down to 363.9 in 2022) which serve to accentuate highlight the need for caution when applying precision to this information.

In another twist, the number of violent crimes in the US in the annual table (what used to be Table 2 but is now Table 1) released in 2022 does not match the data on the CDE’s Data Discovery Tool. The FBI points out these discrepancies on the CDE, noting: “Just as the data in the tables of the annual publications sometimes differ from those available in the master files for the same year, the data in the publication tables may also differ from those released on the Explorer Pages of the CDE. These variations are due to the difference in methodologies between the publication tables and data displayed on the CDE.”

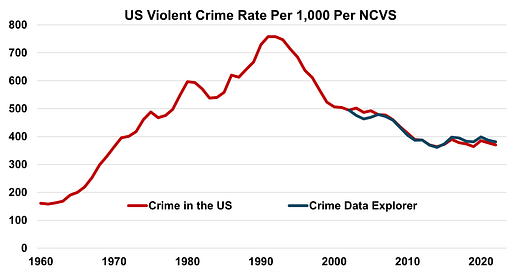

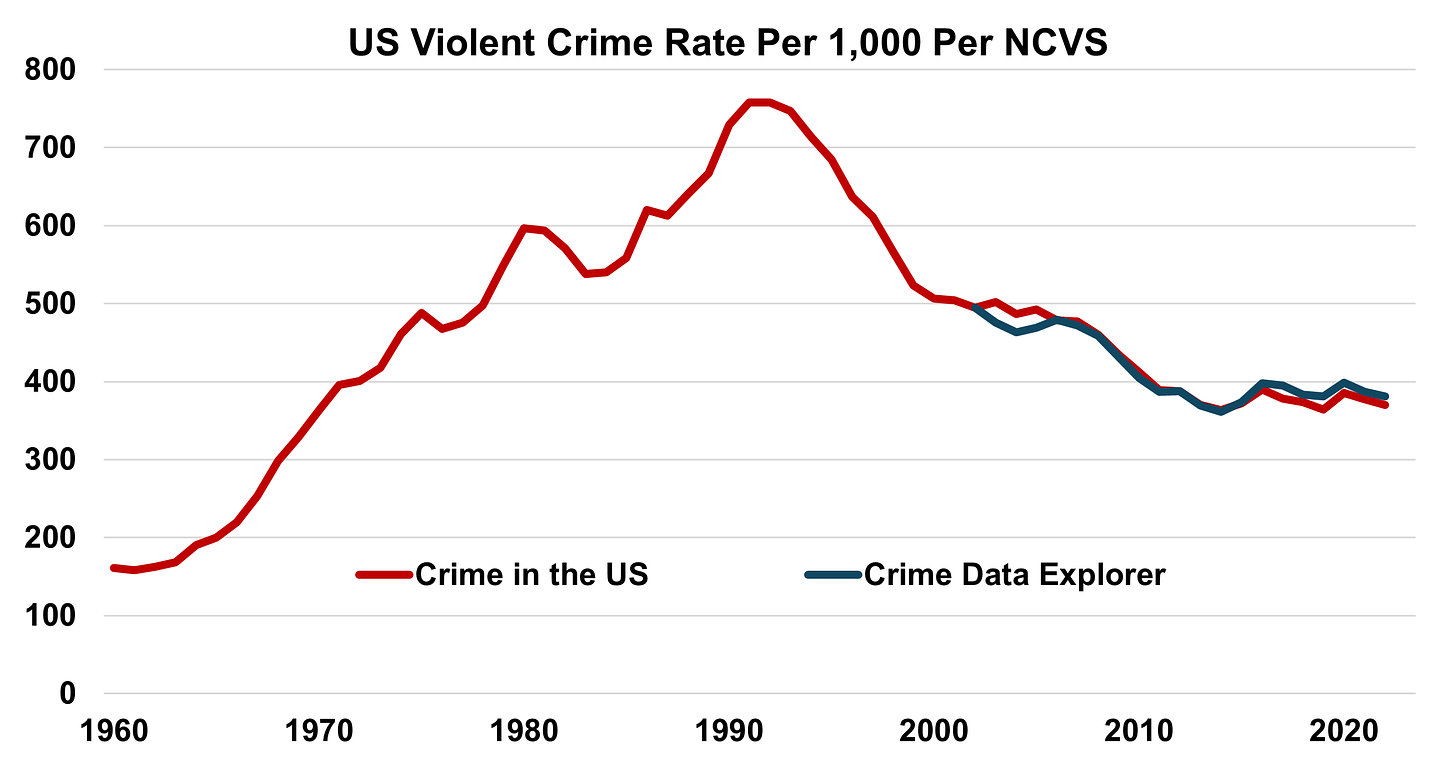

Applying those variations between 2003 and 2022 to the nation’s reported crime rates shows that the differences between what’s being reported in the Crime in the US and what is currently on the Crime Data Explorer are real but relatively slight.

The decline in violent crime since the 1990s and relative stability over the last 10+ years also shows up in the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). A methodological change in NCVS makes it impossible to compare surveys in the 1990s to previous surveys, and NCVS and UCR disagree on what happened in terms of violent crime in 2020 and 2021 (two years that were particularly challenging to survey I might add), but the general contours of violent crime in the US over the last 30 years is largely the same in both measures with violent crime in 2022 being near but slightly higher than it was in 2019.

Given these challenges, here are three pieces of wisdom I have to offer to others when writing or talking about national crime data:

Always remember that reported crime data is inexact, and that’s not even taking underreporting into account. Murder is probably more exact than other types of crimes, but these are all estimates where general accuracy — rather than exact precision — should be the goal. If one year’s crime total rose by 1 percent from a previous year then I prefer to say “crime was roughly even or slightly up” rather than giving an exact figure (please don’t go hunting for things I’ve written that violate this rule!).

When talking about crime data, estimative language is our friend! Hopefully it comes through when I write about crime data, but people should almost always lean into the uncertainties inherent in the data. This is especially true when the data is preliminary, but it’s also true about the final year-end data. One can speak definitively about murder being down 11.8 percent in 213 cities with available 2023 data, but when estimating the national trend it’s important to acknowledge some uncertainty about what it means for the big picture.

Don’t sweat the small stuff. Is Table 1 right that the US murder rate was virtually identical in 2020 and 2021 or is the CDE estimate that murder rose ever so slightly in 2021 right? They both are, neither is, there’s no way to say for sure. Don’t worry if different data sources aren’t in total agreement of the exact numbers, especially if the overarching trends are borne out in the data. Murder rose enormously in the US in 2020, was roughly even in 2021, fell in 2022, and appears to have fallen substantially in 2023 though we won’t know for sure how substantially for a few months. The trend is what matters, not the exact numbers for each year.

Regardless of the exact figures, violent crime — murder, which makes up a tiny portion of overall violent crimes, notwithstanding — in the US has fallen mightily since the 1990s and remains at or near levels not seen since 1970 as we await formal figures for 2023. This is true whether you’re using the Crime in the US report, the Crime Data Explorer, or the National Crime Victimization Survey1.

Reported crime rates prior to the methodological change in NCVS were lower than after the change, so I believe in this assertion even if we don’t have the exact figures. For an explanation of the change see the bottom of this report: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/Cv93.pdf.

From my "Violent And Property Crimes In The US":

Context-Historic Lows Before 2015 (the year violent crime increased by 28 percent over three years per the Bureau of Justice Statistics-National Crime Victimization Survey.

You will hear from a variety of sources that violence in 2022 and 2023 is far below that of previous decades which is true yet fear of crime (see below) is currently at record highs.

There is also data indicating that most Americans are victimized by crime each year if you include violent, property, identity theft, and cyber crimes. Repeat victimizations may have an impact on understanding these numbers.

A pattern of crime increases for some (not all) years seems to begin in 2015. See the yearly summation below.

Data from the National Crime Victimization Survey state that we were at record historical lows for criminal activity. From 1993 to 2015, the rate of violent crime declined from 79.8 to 18.6 victimizations per 1,000 persons age 12 or older.

From 1993 to 2021, the rate of violent victimization declined from 79.8 to 16.5 victimizations per 1,000 persons age 12 or older.

According to FBI numbers, the violent crime rate fell 48 percent between 1993 and 2016. Using data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (National Crime Victimization Survey), the rate fell by 74 percent during that span.

Best, Len.

Superb piece as always.