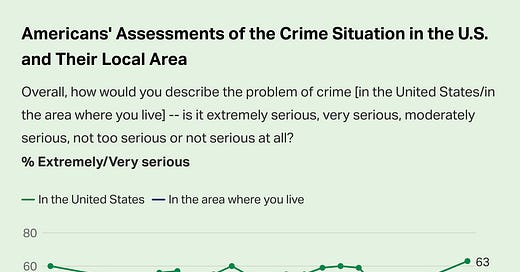

Gallup recently came out with their annual poll of American perceptions of crime trends and it’s a real doozy. Gallup has asked Americans how they would describe crime in the United States and locally every year since 2000, and a record 63 percent of respondents described crime in the United States as “Extremely Serious” or “Very Serious” in the most recent survey (conducted in October 2023). Moreover, 77 percent of respondents said there was more crime in the US than there was a year ago, largely on par with recent years.

This problem seems reasonably unique to crime. If you polled Americans on who won the World Series this season you’d probably get mostly right answers, or at least people would be easily able to look it up and provide the correct answer.

So why are Americans so bad at perceiving crime trends? Did a majority of Americans really think crime rose in 2014, the year with the lowest violent crime and murder rates recorded since 1969?!

I came up with five factors — presented below in the order I wrote them — that I think most likely explain this phenomenon. There are undoubtedly other factors, but these are the ones that speak to me.

“Crime” is poorly defined.

The crux of the problem is that there is no definition of crime provided by the survey. “Crime” could mean UCR Part I major crimes (murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, theft, and auto theft) that are the only types of crime formally measured nationally each year by the FBI. Beyond that, there are NIBRS offenses — both Group A and Group B — and UCR Part II offenses which are criminal but for which we have no national estimates to say whether they're rising or falling from year to year.

Most UCR Part I offenses are property crimes, but respondents may be thinking of violent crimes when they're asked about crime. Violent offenses carry a higher societal burden and tend to make up the crux of most crime reporting by the media. Or respondents might be thinking of murder, the crime with the highest societal cost but which makes up around 0.2 percent of all UCR Part I incidents each year.

This distinction matters quite a bit because “Crime” as measured by UCR Part I has been falling steadily for decades (though, ironically, they increased in 2022 due to increasing theft and auto theft and likely artificially low property crimes during the pandemic).

Violent crime has fallen considerably from the 1990s and it fell in 2022 to one of the lowest rates in decades while murder surged up 30 percent in 2020 and increased again in 2021 before falling in 2022 and (almost certainly) 2023.

Different respondents can mean different things when they say “crime” is extremely serious or whether “crime” rose or fell in the last year. Some years there may not be an actual right or wrong answer to such a vaguely defined questiob.

The Questions Are Hard To Answer

Those saying crime rose in the last year were technically correct in 2022 based on UCR Part I crime data, but if they meant violent crime or murder then they were wrong.

But that’s just going based on reported major crimes. There’s no national estimates of less serious crimes like vandalism or embezzlement. And most crimes that occur do not get reported to the police according to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS).

NCVS does not include murder because it’s a survey, but the 2022 version of NCVS pointed to a sizable increase in violent crime that year relative to 2021. This flies in the face of what we see in reported crime and certainly creates some questions about what we know about American crime rates.

Additionally, violent crime and murder were largely flat or down slightly between 2000 and 2019 making it even harder for an average American to say whether these crimes are going up or down in a given year. Can you really expect a random American to correctly know this year’s crime trend if murder fell 1 percent from last year? That's way tougher than if it surged of plummeted in a year.

There’s certainly less crime in the US in 2022 than in the 1990s, but it’s much tougher to gauge whether there’s less crime this year than last.

The Data Is Hard To Come By

There are 18,000 law enforcement agencies that report crime data to the FBI every year, but this data is only formally reported annually after a lengthy delay. Some agencies publish their own data online, but only a few do that. Our YTD murder dashboard has data from roughly 170 agencies, less than 1 percent of the existing total, so most Americans couldn’t use hard data to know whether reported crime is going up or down in their locality even if they wanted to.

This problem is particularly acute with small cities and rural counties, so it shouldn’t be a huge surprise to see 81 percent of rural respondents saying there was more crime than there was a year ago. People are predisposed to use vibes rather than data to evaluate crime trends because quick access to clear information about those trends has never really been a thing in most places.

The Media Doesn’t Cover The Planes That Land

People are often forced to rely on anecdotes for their perceptions of crime trends which means they're overly reliant on the media and websites like NextDoor. I first heard the above saying from Chris Hayes and it could not be more true of crime coverage.

There are rarely stories highlighting days where a murder did not occur, only when they add up to an unusual streak does the absence of crime become a media story. On the flip side, most murders will get anecdotally reported in the media and people are forced to remember whether they heard more anecdotes this year compared to last year. It’s virtually impossible for people to get right.

Moreover, the spread of social media and video technology has made it infinitely easier to film and publicize a viral crime incident such as a large scale shoplifting spree. There are millions of property crimes occurring each year, but these outlier incidents become the glue people rely on when guesstimating whether crime is up or down. My neighbors never post on NextDoor how many thousands of packages they successfully receive, only video of the one that randomly got swiped.

Partisanship

This is probably the explanation that people go to most often, and it appears to be with good reason. The Gallup poll has broken down the share of respondents by political party (I'm ignoring independents here) which shows partisanship taking hold of this question around the George W Bush administration.

The question was only asked once during Clinton’s first term (in 1996) but the parties largely were in lockstep as crime of all kinds fell rapidly throughout the latter 90s. Starting in the 2000s, however, the question appears to have becomemore partisan. Democrats said crime was rising throughout Bush and Trump’s tenure while Republicans said crime was rising through Obama’s time in officer (despite most types of crime reaching modern lows during that span).

Of course, 91 percent of Republicans saying crime has risen from last year in 2023 basically breaks the graph and takes the partisan bias of this question to new heights.

Conclusion

Partisanship plays a role in this survey’s results, and the 2023 figures suggest the role is larger than ever before. But the share of Democrats saying crime rose in the last year is also higher than at any other point in the survey’s history, so it can’t all be partisanship.

None of this would be possible without a data vacuum leading to anecdote — rather than data — driving what people think. Combine that with the increasing spread of social media, a poorly defined concept, and media hyperattention to viral outliers and you get an environment for public opinion to detach completely from reported trends.

And that, in my opinion, is why people are so bad at perceiving crime trends.

Or maybe it’s because people have lost faith in the system. They are victimized but no longer report it And the no longer participate in government surveys.

“. A sweeping poll commissioned by The Chronicle drew sobering results: Nearly half of respondents said they were victims of theft in the past five years, while roughly a quarter were physically attacked or threatened. The majority had negative impressions of law enforcement.”

https://www.sfchronicle.com/sf/article/sfnext-poll-crime-sfpd-17439346.php

This is excellent and a discussion that is sorely needed. I would only add that the right-wing media's uber-focus on crime in cities is designed to (and does) increase racism. Racism is a key to their in-group/out-group political strategy. So, sure, Republicans perceive a lot of crime because it is intentionally spoon-fed to them. Democrats perceive it mostly because of the mainstream media's "if it bleeds it leads" and legitimate media's desire to keep up with the popularity of Fox News et al.