Thanks to those of you who sent in questions. We had enough that I didn’t have to ask my mom to send in a question about how handsome her baby is (I’ll keep that one in my back pocket). The questions were really good and not of the softball “how are you so effective?” variety that I was expecting, so it took a while to answer. As a result, I couldn’t get to all the questions as it took me forever just to properly answer 4 of them!

Anyhow, without further adieu, let’s dive in!

A while ago you linked to a dashboard for traffic violations, noting that the volume of citations fell in 2019 and coincided with the 2019 cyber attack. However, it looks like volume of traffic tickets remains low. Any insight into why so few tickets have been issued since 2019?

This question references the New Orleans City Council traffic stops dashboard, and the answer tells the story of policing in New Orleans over the last 5 or so years. Below is the graph of traffic stops in New Orleans rolling over 365 days. It shows reasonably steady rates from 2015 to the end of 2019 (up and down, but steady) with a big drop in 2020, a slight rebound in 2021, and a slow but steady decline over the last year and a half.

Next let’s take that graph but make it rolling over 30 days and annotate it with events that might be impacting stops. This shows that a number of different factors caused traffic stops to drop, beginning with the ransomware attack in December 2019, followed by the COVID shutdown, a few months of what has been described as de-policing in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and accompanying social upheaval, and Hurricane Ida. Then, finally, increased attrition and an inability to replace lost officers has slammed NOPD’s ability to perform functions like traffic enforcement. There were over 1,200 NOPD officers and recruits before the ransomware attack, there are under 940 today.

We hear very little about non-fatal shootings. Were it not for the skill of the doctors at University Medical Center the situation in New Orleans would be much worse than it is and would rank us as probably the most dangerous city in the entire world. Would you agree?

The question about the degree to which improved medical care is tough to answer because we don’t have national data on nonfatal shootings and the few places we do have data rarely have data beyond the last 10 to 15 years (if that). Additionally, many factors likely contribute to whether a shooting is fatal.

That said, I talk about non-fatal shootings all the time! My first piece for FiveThirtyEight nearly a decade ago was about non-fatal shootings! And I looked at differences in shooting fatality rates for a later piece.

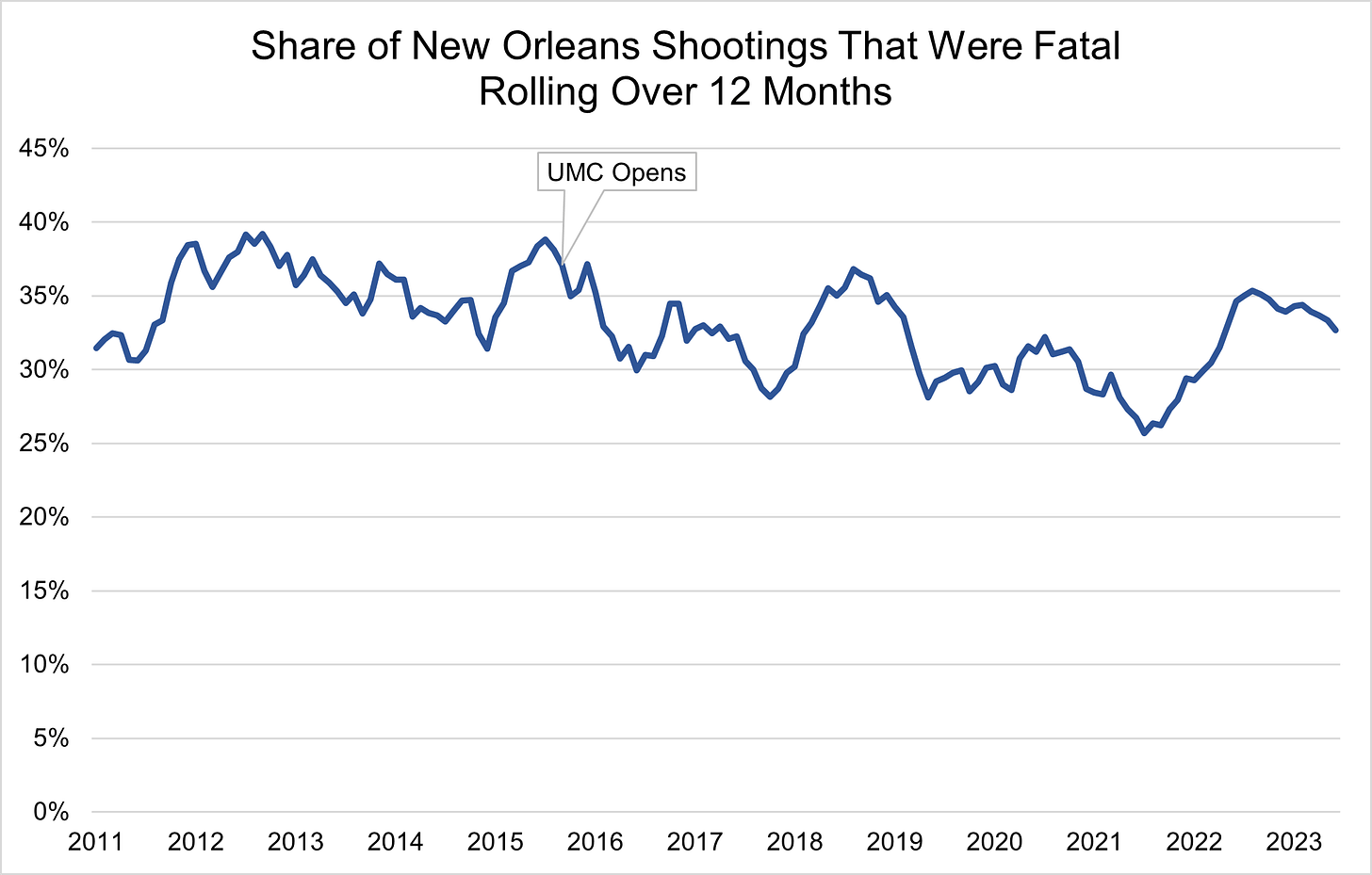

But you want to talk about New Orleans and University Medical Center (UMC). UMC opened in August 2015 as the New Orleans region’s only Level 1 Trauma Center. The data we have suggests UMC has had some impact on the share of shootings that are fatal as 35.4 percent of shooting incidents between 2010 and July 31, 2015 were fatal compared to 31.4 percent since. The graph below shows a subtle change over the last 8 years but it is definitely there.

The caveat, of course, is that we only have shooting data available back to 2010. Just over 30 percent of shootings were fatal in 2010 before that figure spiked in 2011 and 2012. It is possible that shooting data from 2008 and 2009 would complicate the story. There have also been sustained stretches since mid-2015 where over 35 percent of shootings were fatal, so there is still a lot of randomness and luck that goes into whether each incident leads to a fatality.

Are different age groups of juveniles seeing particular spikes in crime? Is there a difference in the prevalence of certain crimes committed by juveniles? How much of the increase in overall crime can be attributed to juvenile crime?

I frequently get asked about juvenile crime and the answer is almost always the same: we largely don’t know. And the reason we don’t know is because measuring perpetrator data relies on arrests and many crimes committed by juveniles (and adults) do not end in an arrest.

Washington, DC provides a good example of this problem. DC has an excellent carjacking dashboard which shows data on the number of carjacking incidents, number of closures, and what share of incidents have juvenile involvement (based on an arrest). There is a clear upward swing in carjackings over the last few years — which, as an aside, seems to be going against the broader trend — and 60 percent of people arrested in a carjacking incident this year have been juveniles.

Seems like very strong evidence that juvenile perpetrators are driving the carjacking surge.

The problem is that only 53 people have been arrested for a carjacking this year while there have been 412 incidents. Some of those arrests may have been for previous year incidents and some of the people arrested are accused of committing multiple carjackings. The share of this year’s carjacking incidents with an arrest is at best 22 percent (92 closures out of 412 incidents per the dashboard) if every incident cleared this year occurred this year, which is unlikely.

If we assume that the 60 percent share holds for juvenile arrests this year then, at most, 55 out of 412 carjackings in 2023 have involved a juvenile being arrested (13 percent). It is very possible that this is a representative sample of all carjackings, but it’s also plausible that these juveniles are getting caught more easily than adult perpetrators.

What’s more, the number of juveniles arrested for carjackings has plummeted so far in 2023 (32 through 6/26/23 compared to 51 through 6/26/22) while the number of carjackings has soared 73 percent in 2023 relative to the first six months of 2022. I’m not sure anyone would point to fewer juveniles being arrested as plummeting juvenile crime, but arrests are the only surefire way to measure juvenile crime.

We definitely see juveniles making up a higher share of vehicle-based crimes in New Orleans (auto theft, carjacking, and vehicle burglary) than other crimes though adults make up a majority of arrestees in all three crimes. But juvenile arrests can be fickle. Consider the below graph of juvenile arrests per year in New Orleans.1 Using arrests as a measure of juvenile crime suggests that juvenile crime was falling over this span, but vehicle burglaries doubled and carjackings nearly tripled between 2015 and 2021.

Long story short, crime data analysis should always be caveated by the strength or weakness of the available data, and never is this more true than when trying to evaluate “juvenile crime.”

I am curious about domestic violence data and the number of violent deaths associated with DV. With the perceived rise of DV during the pandemic it highlighted the lack of good DV data in many communities. Is someone doing a good job with this? Are you able to filter DV homicides in major cities to see trends?.

There is decent evidence that domestic violence rose during the pandemic though I’ll leave it to academics to properly weigh how strong the evidence is so far. I’m happy to be wrong about this, but I’m not aware of any good source of national data on domestic killings.

Some cities do a somewhat decent job of reporting this kind of data quickly while most do not. St Louis and Kansas City, for example, both produce daily homicide analyses that break down the motive for every murder. Domestic violence makes up fewer than 5 percent of this year’s murders in both cities, but the real problem is that many murders have an unknown motive. 60 of 97 murders this year in Kansas City have no reported motive while 45 of 82 murders in St Louis are listed as unknown motive.

The best available data for evaluating murder motives nationally would be the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Report, but agencies are sometimes very bad at reporting relationship data to SHR. In 2020, 91, 89, and 84 percent of murders in New Orleans, Detroit, and Baltimore respectively were reported as an unknown relationship between perpetrator and victim.

Nationally, 53 percent of murder victims in 2020 had an unknown relationship with their perpetrator with the second most common relationship being ‘acquaintance at 12 percent. According to SHR, 15 percent of all murder victims ‘in 2020 had a reported familial connection with 6.8 percent of victims being in a relationship (spousal or dating) with the perpetrator. How accurate that figure is though is anybody’s guess.

The transition to NIBRS could, in theory, improve our understanding of domestic violence in the US, but if agencies do not individually collect and report this data then NIBRS won’t do much on that end.

From a presentation I did for the New Orleans City Council.