Walking in Memphis Crime Data

Ma'am, I am tonight.

The deployment of Federal law enforcement to Memphis began at a time of falling crime in the city making it somewhat difficult to tease out the impact of the intervention on the city’s crime trend. The reported downward trends have accelerated over the last few weeks, but there’s reason to be cautious and not read too much into the most recent data.

The government deployed law enforcement assets to Memphis at the end of September. This deployment was bolstered by around 150 National Guard in mid-October. The National Guard were sent to “support violent crime enforcement” though the police chief in the above article that they are not patrolling, conducting traffic stops, making arrests, or issuing warrants.

The far larger impact undoubtedly comes from the deployment of around 1,500 other Federal personnel from more than a dozen agencies. This is a large deployment on paper considering that MPD reported having just under 2,000 officers in 2024 though the exact makeup of the deployment hasn’t been publicly disclosed as far as I know.

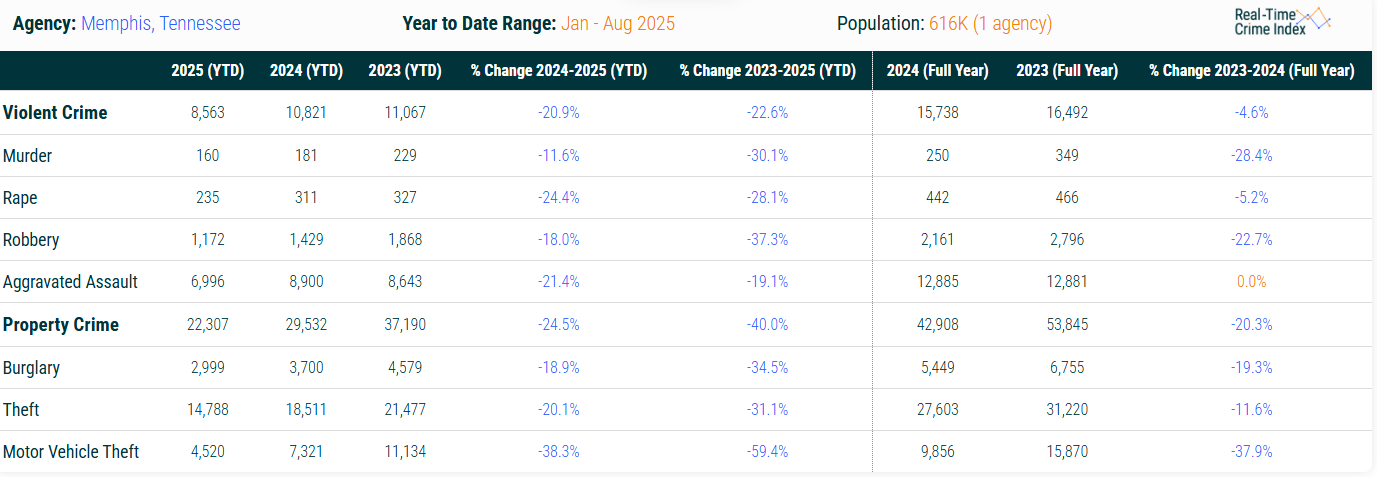

Crime was falling in Memphis prior to the deployment. The Real-Time Crime Index prior to the deployment shows large, across-the-board, drops in crime in Memphis through August 2025. This is an impressive drop that largely matches or exceeds the national trends.

Many types of crime in Memphis were at or near 50 year lows through August — prior to the deployment — reflecting a national trend occurring this year.

You may remember hearing nearly identical language to how I described Memphis when I discussed Washington, DC crime trends a few months ago. Like DC, Memphis also has solid open data that allows for a more detailed evaluation of the city’s crime trends than just looking at the raw numbers alone. Most types of reported crime in Memphis peaked in 2023 or the first half of 2024 and have been falling for most of the last 12 to 24 months prior to the intervention.

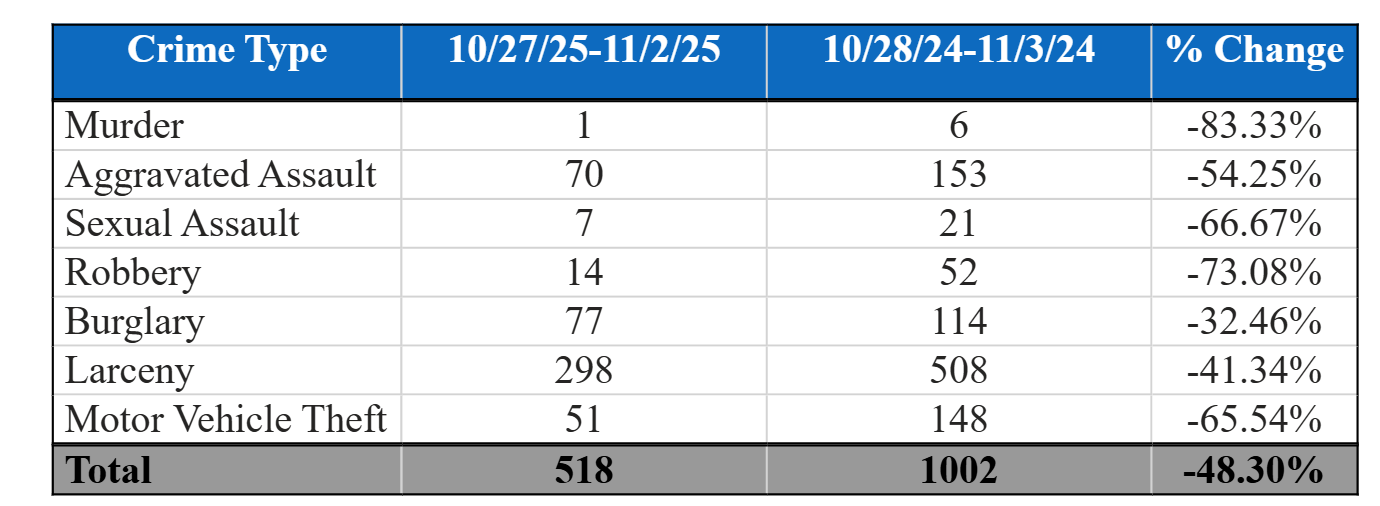

Looking at the incident-level data from the Memphis public feed — which feeds the city’s crime dashboard — shows that crime in Memphis has fallen off a cliff in the last few weeks. Here is a screenshot of the most recent week of data from the city’s dashboard:

That comes across as enormously impressive, but a deeper examination of the city’s crime data raises questions that I cannot answer about whether the drop is accurate or represents underreport of recent offenses from the agency.

Possibility 1 is that the drops shown in the Memphis open data reflect real drops in crime. Crime was falling in Memphis and that decline accelerated in the wake of the Federal deployment. Possibility 2 is that the drops are real but exaggerated by some changing in reporting.

Let’s start our deep dive with murder which plunged in August and the first part of September before rising slightly in October.

Now, the common wisdom is that “it’s hard to hide a body”, so the murder figure may not be plunging during the Federal intervention because it’s the only crime count we can trust. The murder count being reported by the police department does appear to be accurate as comparing it to the number of fatal shooting victims rolling over 30 days in the independently collected Gun Violence Archive shows nearly identical trends.

Murder may not be down, but looking at all shooting victims over 30 days in the Gun Violence Archive shows a strong drop in shooting victims starting at the time of the intervention. This suggests that the reason that murder isn’t dropping is largely due to randomness as the number of total shooting victims has fallen precipitously since the Federal deployment began. A higher-than-normal share of those shooting victims were fatally shot for a few weeks in October leading to the small increase in murder in mid-October relative to September levels.

The recent drop in shootings came at the tail end of a large decline Memphis gun violence that started in May. If that sounds familiar, it’s because it is largely the same language I used describing gun violence in DC a few weeks ago. Showing Memphis and DC shooting victims rolling over 30 days provides perhaps a glimpse into the future of Memphis gun violence as the number of shooting victims in DC has largely returned to the pre-intervention trend after a sharp initial drop.

So, murder isn’t really dropping, but it’s low (relative to the city’s historical standards) and shootings are down. Overall shootings is a much better metric for evaluating gun violence than just relying on murders. Simply put, gun violence in Memphis was steadily falling prior to the Federal intervention, but there was almost certainly a drop after.

What about other types of crime?

Rolling the other five non-murder UCR Part One offense categories that Memphis reports (incident-level data on rape is not reported) shows the peak and decline through much of 2025. Like DC, reported crime was falling in Memphis prior to the Federal intervention.

This steady drop was followed by a fairly massive decline across all crime types but murder beginning in September 2025 and appearing to level out in the first few days of November. This trend is seen in the below charts rolling over a shorter 30 day timeframe.

There’s a chance these numbers are incomplete and the more recent figures will rise, but I’ve been refreshing the Memphis data periodically for a few weeks and the only figures that change dramatically from day to day have tended to be the most recent two days.

Robbery went from 135 in August to 103 in September to 69 in October. To put that figure in historical context, that would be the first time with fewer than 100 robberies in a month since 1972 and the fewest monthly total since 1971.

There were 427 and 432 motor vehicle thefts in August and September 2025 respectively (down from 1,084 in May 2024), but just 193 in October. Aggravated assaults fell from 545 in July to 512 in August, 437 in September, and 323 in October — the lowest monthly total since 2003.

These drops are astounding across nearly every crime group which gives me pause. To see why, I compared the number of aggravated assaults per month (a UCR Part I offense) to the number of non-aggravated assaults per month (not UCR Part I offenses) in the city’s open data. The latter includes simple assaults — assaults with no weapon or serious injury — and intimidation assaults, defined here.

There were right around 3ish non-aggravated assaults per aggravated assault pretty much every month between January 2023 and July 2025. That figure has skyrocketed in each of the last two months — beginning in September before the Federal deployment — reaching roughly 5 non-aggravated assaults per simple assault in October.

Looking at it another way, aggravated and non-aggravated assaults in Memphis have tended to move in the same direction in recent years. Not always exactly so, but a gap opened up in the first part of this year which has become a chasm. Notably, this gap opened up in the first half of the year and has gotten much wider over the last few months. I may be reading too much into this, but it certainly stands out as strange.

The trend persists (though slightly less aggressively) when comparing domestic violence simple assaults to domestic violence aggravated assaults. I wouldn’t expect domestic incidents to be dramatically impacted by a surge in Federal law enforcement, but that assumption may also be wrong.

Robberies, thefts, and motor vehicle thefts all plunged to new lows in the last few weeks while burglary fell from a higher level. That’s frequently a tell-tale sign of some sort of change in reporting or underreporting given the consistent imperfection of crime data reporting, though perhaps in this case it does just reflect an actual change in crime caused by a sizable enforcement intervention.

None of this means crime data is being intentionally manipulated. Sometimes a large drop in crime is a large drop in crime.

The Memphis data shows a clear increase in enforcement-related activity, almost certainly driven by the deployment of Federal law enforcement.

An early November PBS article reported that around 1,500 arrests had been made by Federal law enforcement in around 5 weeks. That’s a large figure given that MPD reported about 3,200 total arrests in October 2024 per Jacob Kaplan’s data. Most of the arrests appear to be warrants or administrative, or at least they were as of mid-October and a lack of transparency about the type of enforcement being carried out makes it difficult the degree to which crime might be realistically impacted by the deployment.

The Memphis open data shows signs of increasing enforcement.

There was also a 33 percent increase in traffic stops in October which can be fairly attributed to Federal law enforcement — by their own admission.

The raw number of arrests from traffic stops increased, but the share of traffic stops with an arrest remained roughly where it has been since Tyre Nichols was killed in January 2023.

And drug/narcotics violations — a good measure of enforcement level — increased to the highest levels since January 2023 (though still lower than pre-2023 levels).

The near-universal (within Memphis) drop in non-murder UCR Part I offenses seems more like a reporting issue than an actual drop in crime. Recent increases in traffic stops had no relationship to changes in aggravated assaults and robberies. And while the zip code of traffic stops in Memphis tends to correlate decently strongly with where violent crime occurs, the increase in October was only loosely connected with the geography of violent crime.

I can’t think of a reason for domestic violence aggravated assaults would plunge because traffic stops went up. Vehicle-based crimes such as motor vehicle theft and vehicle burglary fell off a cliff.

It might make sense that an increase in traffic-related enforcement would lead to fewer vehicle-based crimes, but those things haven’t been tied together in Memphis in the past few years of available data.

As I said, none of this means that crime data is being intentionally manipulated. It could all be correct. We also run into underreporting all the time and usually — but not always — it gets corrected. Some crimes — like burglary and robbery — clearly started dropping began before the deployment while others are more exactly aligned to the timing of the deployment.

Reviewing this data reminded me of an issue we ran into with the Real-Time Crime Index when we were getting started. We got data from a state for a large police department that showed an enormous and sudden across-the-board drop in every type of crime.

Sensing something was amiss, we reached out to the agency and set up a meeting to discuss. At the meeting we noted that the agency’s crime counts to the state appeared to be underreported and asked if it was possible to get corrected data. The agency was taken aback that their numbers were wrong, they simply had no idea.

They researched and found they had a backlog of thousands of cases that were stuck in ‘Pending’ status. The agency identified and fixed the problem and is now reporting correct data to the state, us, and FBI. There was no malice and the agency was clearly incentivized to fix the problem once it was found.

Much as there are data reporting issues with respect to DC’s public feed, there could be reporting issues coming from Memphis (though the agency’s public data feed largely matches what is being sent to the FBI). Or these could reflect genuine declines in crime across every measured type except for murder (and rape which is down on the dashboard but we don’t have that data).

Like with DC, having access to 911 Calls for Service data would help answer my skepticism and help explain some of these discrepancies. Alas, that data isn’t publicly available and I haven’t had luck getting it through public records requests just yet.

I feel confident in the assessment that crime in Memphis was falling prior to the intervention. Shootings clearly fell faster after the intervention. This trend seems similar to the what was ultimately a short-lived drop in shootings in DC, but is the closest thing we have to a clear change potentially tied to the deployments themselves. A surge in law enforcement leading to a short-term drop in gun violence would make a ton of sense.

Everything else seems a bit more questionable in my opinion though. These things happen sometimes with crime data, but it usually isn’t potentially a big deal nationally.

Is crime down in Memphis? Almost certainly, and that decline likely continued through the first month-plus of the Federal deployment. I have far fewer qualms about the pre-summer data which showed the clear, steady drop that began in 2023 and 2024 was extending into 2025. It’s not hard to believe that crime in Memphis continued to fall — and maybe even accelerated — following the Federal deployment.

But did crime fall as sharply in October as the public data and the city’s dashboard suggest? Much like DC, I’m somewhat skeptical. Maybe I’m reading too much into things, but it certainly does look that at least the way aggravated assaults are being reported is different (a change that may predate the deployment). I’m open to the idea of being completely wrong and that crime fell an immense amount in October 2025, but the proof is not quite yet in the Rendezvous BBQ sauce.

Ultimately, more time is needed to better understand the city’s medium and longer term trends and determine the impact of the Federal deployment.

This Week On The Jeff-alytics Podcast

Have you listened to the most recent pod? I talk with NYU professor Anna Harvey about her amazing Jail Data Initiative (and other projects). It’s a fun listen, so check it out!

Nice Marc Cohn reference, Jeff.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PgRafRp-P-o&list=RDPgRafRp-P-o&start_radio=1

I may be misremembering my Crim. classes from 30 years ago, but violent criminals, domestic or otherwise, are often the same people who also commit non-violent crimes, who walk around with outstanding warrants for other crimes, violent or no, and are the same people who commit regular traffic infractions. Any increased law enforcement effort into warrants and traffic (which leads to warrant discovery) is going to drive down most other crimes just by incapacitating those particular impacted criminals from being able to commit other crimes, at least temporarily. Homicides which are retributive crimes of opportunity (there's that SOB!) or against a domestic partner (where even a cop driving by isn't going to deter much less discover the crime in progress) are going to be less impacted, except inasmuch as one or the other participants in an ongoing beef, or the violent spouse, might be swept up for a warrant, temporarily delaying the outcome?