Under The Clearance Rate Data Hood

The obnoxious path to analyzing clearance rate data.

I had a guest essay in the New York Times last month about clearance rates that I’m sure you’ve already read (but go read if you haven’t!). The gist of the piece is that reported clearance rates for all crimes have fallen in an unprecedented fashion since 2019 with rates for murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, theft, and auto theft reaching the lowest levels ever reported in 2022 (the burglary clearance rate has also fallen but not as dramatically).

Clearance rates were stable for most of the last 30+ years: 45.6 percent of violent crimes were cleared in 1990 compared to 45.5 in 2019. But that all changed in 2020 with the violent crime clearance falling to 41.7 percent that year, then 39 percent in 2021, and 36.7 percent in 2022.

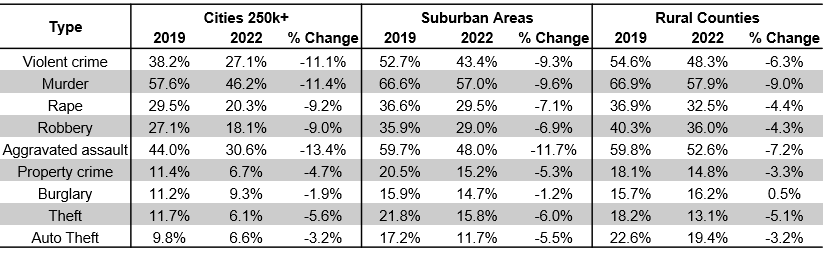

Moreover, the decline occurred pretty much everywhere. The violent crime clearance rate fell 11.1 percent in big cities and 9.3 percent in suburbs.

The NYT piece is all about the declining clearance rates, so please give it a read if you’re so inclined. Today’s post is about the data underpinning the analysis which can be quite difficult to aggregate.

Clearance rates are estimated by the FBI each year using data reported by agencies participating in the Uniform Crime Report. Not every agency reports clearance data to the FBI every year — even if they report crime data to the FBI. Chicago, for example did not report clearance rate data for any year between 1994 and 2021 even though they reported crime data to the FBI every year but 2021.

Clearance rates — like almost all crime data — are flawed statistics, but they are consistently flawed and we have no reason to suspect they suddenly became more flawed midway through 2020.

National clearance rate data is tough to come by because it is not kept in a single repository or report. Finding clearance rate data from 1995 to 2019 is relatively easy. All you have to do is click on the year you want on the FBI’s Crime in the US website, navigate to the clearances section, and find the table covering “Percent of Offenses Cleared by Arrest or Exceptional Means” which is usually Table 25. You have to collect the data year by year, but it’s at least a straightforward process.

Getting data for 2020 and 2022 (more on 2021 later) is more obnoxious. To do that you have to go to the Crime Data Explorer download page, find the Crime in the United States Annual Reports section (fourth section from the top), select the Offense Known to Law Enforcement collection, download it for the year you want, pick up the kids from school, help with their homework, make dinner, remember to open the downloaded file, open the folder for Tables 25-28 Clearances, and there you have the exact same Table 25. It's the same data but the process is far less intuitive.

The clearance rate data for 1960 to 1994 is much more challenging to access because it exists only as scanned-in PDFs. They can be found on Archive.org (here is 1970, for example). The table is the same conceptually, but it is never in the exact same place within the report so it takes some work to find.

That’s a pain, but it’s doable for every year from 1960 to 1994.

Then there is 2021.

The switch to NIBRS meant that there was no Table 25 with which to get an apples-to-apples clearance rate comparison in 2021. My solution — which I detailed a few months ago — was to use agency-level data to estimate national clearance rates. Not perfect, but the best possible methodology given the data constraints.

Agency-level data is reported by month which allows us to evaluate not just the decline in clearances, but say when it appears to have begun.

One challenge to working with monthly clearance data is that not every agency reports each month. Some report quarterly, some report annually, and some just skip full years. A rolling graph of clearance rates over 12 months will largely solve that problem by accounting for agencies that only report once or a few times a year.

Two other problems with using agency-level clearance data are Illinois and Florida. These two states have extraordinarily erratic reporting patterns with Florida’s changing from year to year and Illinois largely not reporting clearance data at all until 2021/2022. Including those two states is extremely disruptive of efforts to identify a national trend.

Taking clearance data from every other state, however, creates a reasonably smooth and accurate look at the national trend. For that you can see the below graphs of the estimated national crime clearance rate for murder, violent, and property crime rolling over 12 months (minus Illinois and Florida).

As you can see, clearance rates were largely stable leading up to May 2020, when George Floyd was murdered, and fell precipitously at that point, remaining steadily lower until the end of 2022. These rates are approximations of what the actual estimates should show, but given the issues of data quality it is the best we can do to highlight a clearly important issue.

Identifying the whats in this manner clears the way for further examination of the whys and what's nexts of the problem.

Interesting. Could part of the issue be the last gasp of the baby boomer officers retiring, driven by Floyd and COVID? A sort of demographic effect? It would be interesting to see the age profile of departments - they were probably boomer heavy, reflecting the general demographics.

The universality of the effect is amazing - causes me to wonder since that would seem to imply it transcends politics.

The most interesting part, to me, is that reported rates of crime are also falling, but every theory of crime I know of expects clearance levels and crime levels to move in opposite directions.

If crime is less often caught and punished, then you'd expect crime rates to rise in response to a lower certainty of punishment. And looking at it from the other direction, if crime rates are dropping, you'd expect clearance rates to rise given the lower workload for law enforcement.

So...what gives? What explains this counterintuitive result? Is the clearance or reporting data so bad that the reality is moving in the opposite direction of the data? Or are these causalities smaller than criminal theory predicts and some other factor is driving the trends?