Murder Remains Down Nationally Through September

Checking in at the start of the fourth quarter.

Murder is down around 12 percent in 165 cities with available data this year, and with only a few months left in the year that figure is unlikely to change all that much. One thing that hopefully sticks out about the preceding sentence is that the size of our sample has grown tremendously, from 100 cities at midyear to 165 today.

There are three reasons why I decided to expand the sample:

A larger sample should improve its predictive accuracy. Data from 75 cities is more accurate than data from 30 cities, and data from 165 cities is more accurate than data form 100 cities.

Many of the places added in the last few months are smaller cities. This should help lessen the manner in which big cities tend to overstate the national trend (more on this in a future post) and whether the decline is solely contained within big cities.

I wanted to understand what the fuller universe of cities with available data looked like. How many cities could we reliably find?

The decline in murder has remained remarkably consistent throughout the year (though, admittedly, the sample has grown over the last few months). Here are the figures through my update on September 30:

March -11%

April -10.2%

May -11.7%

June -10.5%

July -12%

August -12.2%

September -12%

There was some weirdness in the last few days of September, with DC going from 199 murders through 9/25 to 214 murders through 9/28 with DC’s open data showing only 7 murders during that time, and Miami adding 11 murders between 9/17 and 9/24 which comes to 16 percent of the city’s total this year.

Still, our sample shows widespread declines across every represented population group. The 250,000 to 1 million group is heavily skewed by large increases in Washington DC and Memphis while the 1 million+ group is skewed by a large decrease in San Antonio.

The uniformity of the decline is a very positive sign. We have data for all 12 cities representing 1 million or more people and over 80 percent of cities between 250,000 and 1 million. The share of smaller cities represented is much smaller though (about 20 percent of cities 100,000 to 250,000 and 1 percent of cities under 100,000).

The change in murder in cities of all sizes tend to correlate strongly with the national change with the group of cities from 250,000 to 1 million and cities under 100,000 tending to have the most predictive value from year to year. At this point, however, we’re getting much more into guesswork considering how little of the smaller cities sample we really have.

There is also some good evidence of a sizable decline coming from the few states with complete or somewhat complete data for 2023. Murder was down 13.5 percent in Utah and down 14.1 percent in Oregon through July (though some smaller agencies may not yet have reported data to those state UCR programs), and fatal shootings were down 35 percent in the 20 GIVE agencies of New York through August.

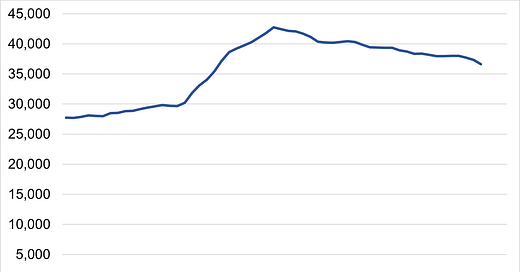

Moving on to the other good source of national data on gun violence — the Gun Violence Archive — shows a continued encouraging trend of falling gun violence. Even more encouraging is the fact that non-fatal shooting victimizations plunged in September relative to September 2022 according to GVA data. Fatal shootings are down roughly 6.5 percent YTD relative to YTD 2022 while non-fatal shootings are down around 5.8 percent.

Overall, shooting victims in Gun Violence Archive data were down 25 percent relative to September 2020 and up less than 10 percent relative to September 2019, before the rise.

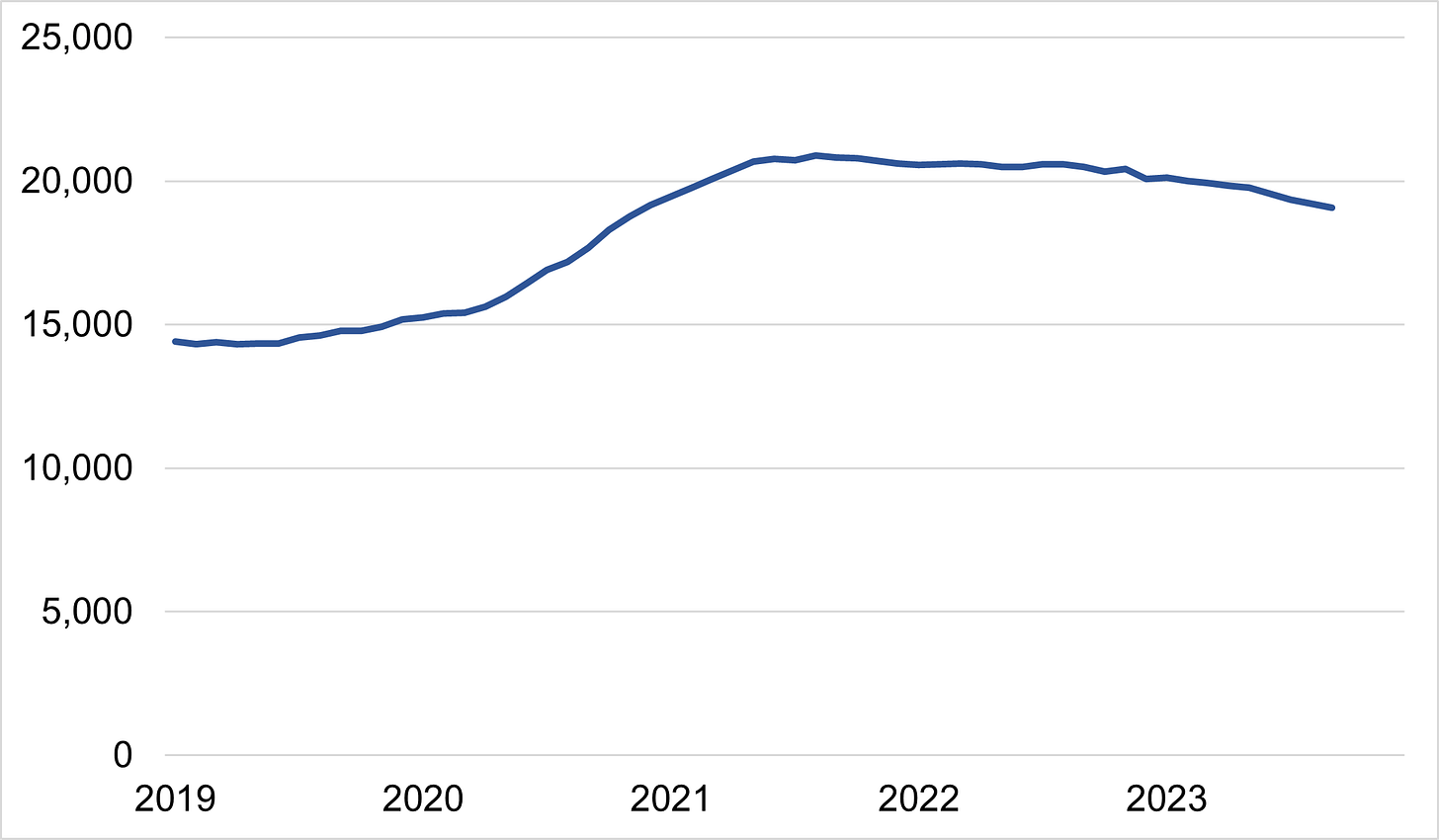

What it all means is that it is becoming increasingly likely that murder will have fallen at or near a historic rate in 2023. Murder has never fallen more than 9.1 percent nationally from one year to the next (data back to 1960) and there have never been a one-year decline of 2,000 or more murders.

Neither milestone is by any means certain this year but both are definitely in play.

The FBI should release its 2022 Uniform Crime Report data in the next few weeks and that should give a better idea of how many murders there were in 2022. That should help to contextualize just how low 2023 might go.

I just listened to Malcolm Gladwell's series about gun crime in the USA, and he suggests that gun crime murder statistics are hopelessly out-of-whack because of the increased ability of emergency departments to save people's lives after being shot. Could it be that the murder rise in the USA during the pandemic was an artifact of hospitals being over-whelmed by COVID patients?