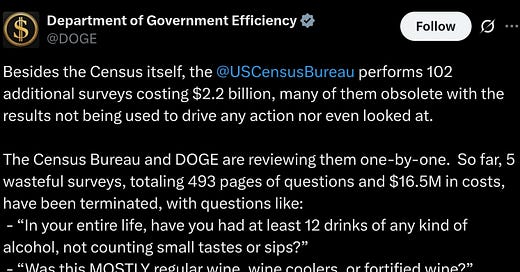

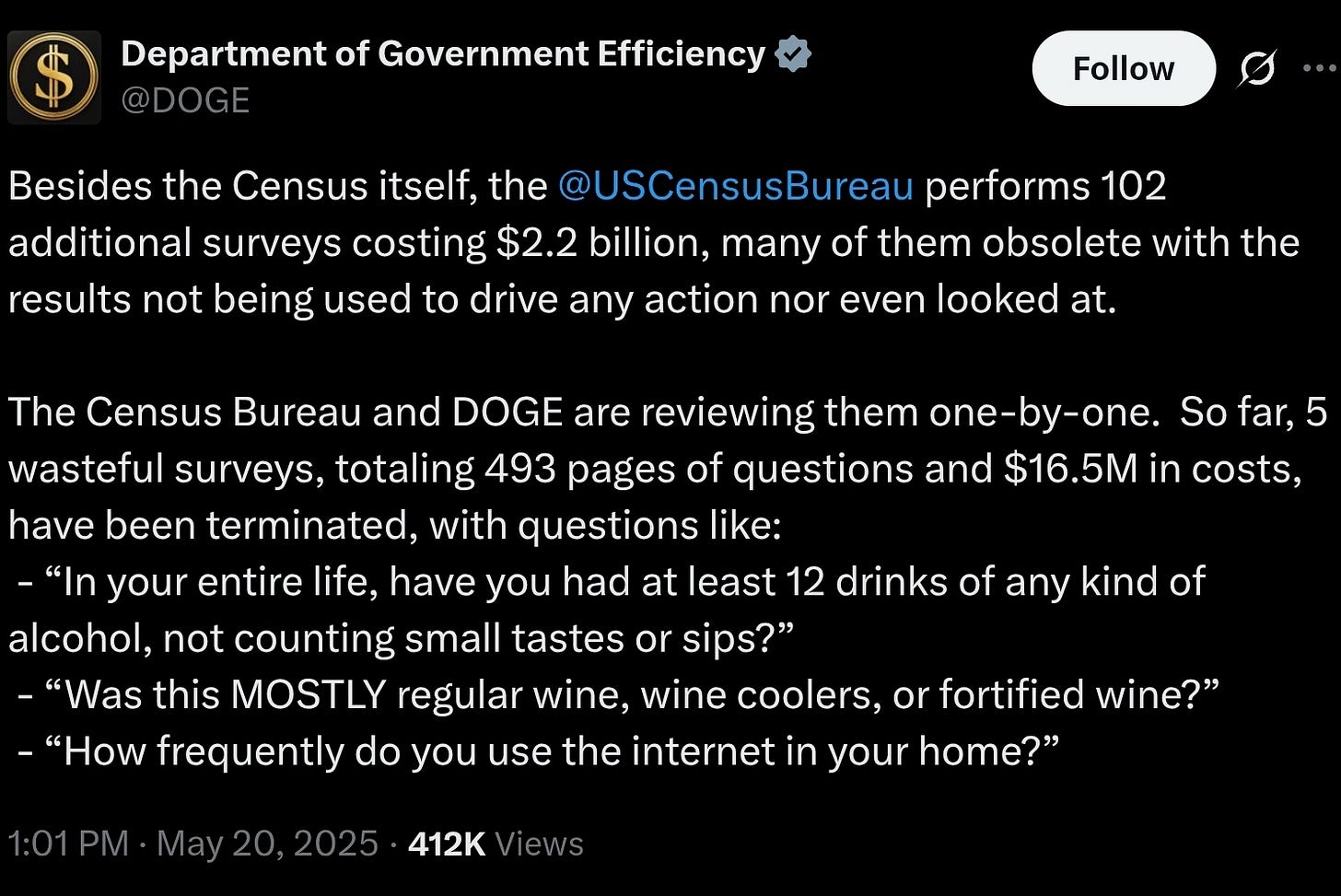

Federal crime data has not noticeably changed in the first few months of the new Administration, but I have heard growing concern that the continued collection of the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) is at risk. The possibility is still speculative at this point, but it feels less speculative in light of a tweet yesterday from DOGE acknowledging plans to review Census surveys.

Getting rid of NCVS would be an enormous error given its critical insights in United States crime trends and it's worth reiterating why.

The United States has two crime measures: the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) and the NCVS. UCR takes data from around 18,000 law enforcement agencies nationwide to estimate the number of reported crimes each year. NCVS, by contrast, is a survey of around 150,000 households that is undertaken by the Census Bureau on behalf of the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). These systems tend to agree about the contours of US crime trends even if they don’t always say the same thing every year.

The NCVS is one of more than 130 surveys conducted by the Census Bureau each year, but it has been understaffed in recent years. Interviews are initially conducted in person with follow up interviews conducted in-person or on the phone per the NCVS methodology. Participants are interviewed every six months. NCVS is one of only a handful of surveys conducted by the Census Bureau that requires field staff for in-person interviews which undoubtedly adds to its cost.

The nature of the NCVS requires a large staff of Census Bureau Field Representatives (FR), but the Census has been struggling to bring aboard sufficient staffing to carry out this task in recent years. A recent report from the Department of Commerce Office of Inspector General found that the Census Bureau “struggles to recruit and retain FRs in some areas, resulting in high FR attrition. This has led to staffing shortfalls for the ACS, CPS, and NCVS.”

The OIG report examined staffing issues through FY 2023, and these issues have no doubt been exacerbated by the hiring freeze implemented on January 20th. The effects of the hiring freeze on Census operations can already be seen in the postponement of a Special Census that was planned for a city in Tennessee. And long-running surveys for other US government agencies are already being scaled down.

That NCVS — which is not statutorily required — might either be formally cut or be unable to be carried out at a sufficiently high quality due to staffing shortages at the Census Bureau is certainly not a done deal.

That said, I have heard rumblings that the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is prioritizing cuts of data collections that are not required by statute, which could mean a cut to NCVS sometime down the line.

Nothing appears to be set in stone, and it’s certainly plausible that no changes are anticipated or planned. But major changes could also come to NCVS, and eliminating the annual report would make no sense for many reasons.

NCVS is critical for understanding crime

It is important to have UCR because murder victims can’t be surveyed, UCR helps standardize crime types everywhere in the US, and UCR allows for more precise monthly and annual estimates of crime counts locally, statewide, and nationally.

NCVS, on the other hand, is essential because it helps to account for crimes that are not reported to law enforcement each year. Some crimes, like murder, are reported at or near entirety while other crimes like rape and theft tend to get systemically underreported.

Relying solely on UCR would be damaging because it would leave the US blind to changing crime trends in crime types that are difficult to measure and it would lessen our certainty as to the overarching trends shown in the reported data.

NCVS is cheap

The entire BJS budget is right around $50 million which is about what Texas alone spends on Crime Records Services to manage its UCR program (amongst other tasks) each year. BJS boasts the 9th largest statistical program in the US government, about 14 times smaller than the Bureau of Labor Statistics and 28 times smaller than the Census Bureau.

I’ve been told that NCVS takes up about half of the BJS budget though I haven’t been able to nail down an exact figure. Either way, this is a pittance to spend on the payoff of a better understanding of the nation’s crime trends.

We spend a ton of money collecting crime data to measure reported crime trends. The NCVS, by contrast, is a relatively cheap method of evaluating unreported crimes and providing context to the reported trends. A $20 million survey sounds expensive, but the gain in our understanding of crime produces benefits that far outweigh the costs.

NCVS aligns with the Trump administration’s stated goals.

There were two documents published on April 28th that paint the picture of an Administration that would like to see an improved national crime data infrastructure. First, the White House published an Executive Order which says that (emphasis below mine):

“The Attorney General and other appropriate heads of executive departments and agencies (agencies) shall take all appropriate action to maximize the use of Federal resources to:

(i) provide new best practices to State and local law enforcement to aggressively police communities against all crimes;

(ii) expand access and improve the quality of training available to State and local law enforcement;

(iii) increase pay and benefits for law enforcement officers;

(iv) strengthen and expand legal protections for law enforcement officers;

(v) seek enhanced sentences for crimes against law enforcement officers;

(vi) promote investment in the security and capacity of prisons; and

(vii) increase the investment in and collection, distribution, and uniformity of crime data across jurisdictions."

The Executive Order does not specifically mention NCVS or UCR, but failing to invest enough resources to carry out NCVS would seem to run counter to the idea of investing in crime data. Both UCR and NCVS are carried out under the Department of Justice umbrella, and it would be nonsensical to increase resources dedicated to one form of DOJ data collection on crime (UCR) while eliminating another (NCVS).

The second document was a policy brief from the America First Policy Institute (AFPI), a non-profit think tank launched in 2021 to further the President’s policies.

The AFPI brief calls for added resources and responsibilities to BJS to align publication of both reported crime trends under UCR and data from NCVS. The AFPI recommendations reflect similar ideas in a recent report from the non-partisan Council on Criminal Justice (disclaimer — I was a part of that working group). Per the brief’s recommendations:

“Designating BJS as the lead agency in the public dissemination of national crime statistics would establish a clear and direct chain of command. This would allow BJS to harmonize the release of NIBRS data (gathered by the FBI from law enforcement authorities) and the NCVS, an annual survey of 150,000 households. As a statistical agency, BJS reports include detailed methodologies, which would make original releases and revisions of crime data more transparent, if required. Adequate funding must be allocated to develop and maintain this structure.”

This is a much stronger endorsement of adequately funding both BJS and NCVS highlighting how this program aligns with the administration’s goals.

It’s not clear what will happen with NCVS and whether the concerns I’ve outlined are overblown or prescient. BJS has already reduced the detail they collect in NCVS, such as removing questions about gender.

These changes are relatively minor but they do decrease the amount of information known about gender-based hate crimes that we know tend to be systemically underreported to police. Losing the entire NCVS collection would mean that the US will obtain a subpar understanding of national crime trends much like what happened in 2021 during the NIBRS transition. NCVS might be difficult to restart as well given that participants participate in NCVS for 3 years.

Poor collection on both reported and unreported crime increases the challenge of effectively communicating about this subject and makes it easier for the misinformed to thrive. Our crime data infrastructure is imperfect and there are important, concrete steps that can be taken to improve it. These steps rely on more, rather than fewer, resources dedicated towards better data on both reported and unreported crime.

Getting rid of NCVS would be a giant leap backwards.

Hi Jeff: Per the Marshall Project, it may be the opposite, see https://www.crimeinamerica.net/will-trump-change-national-crime-statistics-are-we-getting-accurate-crime-data/.

Trump consistently cited the NCVS during the campaign. Yet the media ignores it. I've had several conversations with reporters on crime who didn't know the NCVS existed.

Regardless, the NCVS (the nation's premier source of crime statistics per the US Census) is invaluable in collecting data far exceeding the crimes reported to law enforcement.

As an analyst, what would you choose, the smaller data set of one that exceeds it by leaps and bounds?

Best, Len.