One of the common responses to my piece from last week on the widespread — albeit preliminary — reported decline in murder and crime could be summarized in the below comment from Twitter:

“How accurate can recent burglary/larceny crime stats be when we know they're not being recorded in many locations where such theft won't be prosecuted? I imagine the same goes for some other stats here.”

Those that are familiar with this newsletter will know that I talk all the time about flaws in crime data (see here, here, here, and here) and how it impacts our impression of trends.

That all crimes don’t get reported to the police is well known. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) for 2022 found that 48 percent of violent crimes (as the FBI defines them) were reported to the police in 2022 and 31.8 percent of property crimes were reported to the police. The fact of underreporting of crime is undeniable. What's unknown is whether a change in the level of underreporting is responsible for the trends we see of falling crime.

The question above isn’t one question but three different questions that are worth addressing. The three questions are:

Is crime underreporting getting worse?

If underreporting is getting worse, should that make us question the overall national trend?

Are prosecutors to blame?

And my answers are “maybe, maybe not, we don’t know”, “probably not”, and “I’m pretty skeptical.”

Is crime underreporting getting worse?

We ultimately cannot answer this question with full confidence because it’s hard to measure something that is not reported. The NCVS gives clues, but it cannot fully answer this question because it is a survey with confidence intervals that make it impossible to say whether underreporting trend has gotten worse over the last few years.

That said, the argument I would make in favor of greater underreporting would revolve around longer response times in many agencies due to staffing shortages.

If an officer takes longer to respond then the likelihood that an incident will be marked Gone on Arrival or Unfounded or Unable to Locate (or whatever verbiage an agency uses to describe an incident where they couldn’t find the victim or caller) rises. Longer response times can obfuscate crime trends though the obfuscation is typically reasonably narrow.

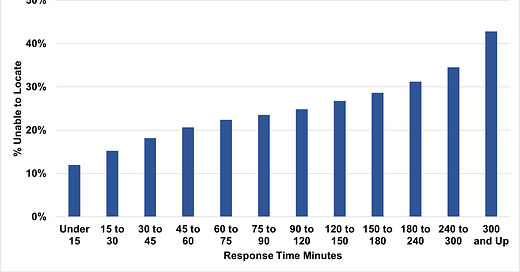

Seattle has pretty good Calls for Service data which lets us break down incidents by response time and disposition. As is clearly seen below, as response time goes up in Seattle so too does the likelihood that a call will be marked “Unable to Locate.”

Seattle has lost a ton of police officers over the last few years and, unsurprisingly, response times have increased from around 51 minutes on average in 2019 to 77 minutes on average this year. As a result, the share of theft Calls for Service in Seattle that have a report disposition has fallen from 66 percent in 2019 to 57 percent in 2023.

Seattle is not alone in losing officers as most cities above 100,000 people lost officers between 2019 and 2022. Conversely, most small cities and counties gained officers between 2019 and 2022.

We simply can’t say for certain whether the problem is getting worse on a national scale though. The share of people who said they reported violent crimes to the police fell from 52.2 percent in 2021 to 48 percent in 2022 per NCVS, but the 2022 share was within the margin of error of 2021’s percentage and largely in line with the 46.5 percent and 49.3 percent reporting rate noted in 2019 and 2020 respectively. Also, the most recent data covers 2022 which obviously says nothing concrete about underreporting patterns in 2023.

Seattle is a bit of an extreme case. Most agencies were roughly around the same number of officers in 2022 as they had in 2019 with over 75 percent of cities with 50 or more officers in 2019 being within 10 percent of that figure in 2022. Only 20 of the nearly 1,300 police departments for cities that had more than 50 officers in 2019 (and reported data for 2022) lost a higher share of officers than Seattle did. And no agency with fewer than 3,500 officers in 2019 had lost more officers by 2022.

Other agencies are also handling having fewer officers better. New Orleans, for example, lost 18 percent of its officers between 2019 and 2022 (44th worst), but the department began employing many more civilians in 2023 which has helped reduce response times. As a result, the share of property crime Calls for Service with a Gone on Arrival disposition has fallen from nearly 40 percent last year to around 30 percent this year.

So while worsening underreporting in 2023 in some agencies may be balanced out by other agencies seeing less underreporting this year (along with many agencies where it wasn’t a problem to begin with). Unfortunately, high quality publicly available Calls for Service data is hard to come by which severely limits our ability to understand whether underreporting got worse in large chunks of the United States or if it was contained in a few extreme outlier examples.

Of course response times aren’t the only reason property crimes don’t get reported (to say nothing of the complex reasons for systemic underreporting of certain types of violent crimes like sex offenses). Many stores don’t report small-scale shoplifting offenses by matter of policy. One would think that, given the increased attention to the issue of “organized retail crime”, that the share of such offenses that are reported by stores would increase rather than decrease.

If underreporting is getting worse, should that make us question the overall trend?

The real meat of the problem — in my opinion — is that if crime underreporting has, on the whole, gotten worse then does that mean the declines seen in the FBI data are wrong? I would say ‘probably not’ for three main reasons.

First, murder is down huge and we know that murder is not underreported. The crime we know to be the most accurately reported is plunging which means other types of crime falling is at least plausible. Reported violent crime trends are pretty strongly correlated with murder trends nationally from year to year, so the fact that murder is down quite large reinforces the likelihood that overall violent crime would follow a similar trend. Murder and property crime are less strongly correlated but they have tended to move in the same direction — more or less — since 1960.

(Adding the disclaimer that 19,000 murders is still a lot of murders even if it's 2,000 below last year. And murder being down in 75 percent of cities means it's even or up in 25 percent. Acknowledging a trend's direction does not mean approving of the current level).

Second, the declines shown in the preliminary FBI quarterly data are quite large outside of auto theft and the impact of underreporting is likely to be reasonably small in the grand scheme of things when calculating the year-on-year change for 2022 vs 2023.

Consider the case of longer response times driving down reports of theft in Seattle. There have been around 11,750 Calls for Service for theft incidents in 2023 in Seattle. If theft Calls for Service were reported in 2023 at the same rate they were in 2022 then there would only be about 146 more theft incidents with a report disposition this year compared to last.

Third and finally, remember that Seattle is most likely an outlier here and most underreporting is going to be occurring in larger cities of 100,000 people or more that have lost officers. The change in crime as suggested by the preliminary quarterly data, however, is very large pretty much everywhere you look. Indeed, the decline in property crime nationwide would be improved if you removed bigger cities that are more likely to have larger surges in auto thefts this year.

Smaller places appear to be following the same declining trend as bigger places in the preliminary quarterly data suggesting that the trend is real and not due to more people refusing to report crimes that occur. It's easier to explain away underreporting in big cities, harder to believe that people are also underreporting crime less frequently in rural counties and small cities.

We can't know for certain whether underreporting is actually worsening. The available evidence points to possible problems some places with possible improvements elsewhere which implies any impact on national trends is likely minor.

Are prosecutors to blame?

Underreporting of crime is happening in 2023 because underreporting of crime always happens. The final part of the initial statement, however, suggested a cause: prosecutors refusing to prosecute.

There’s obviously no way to know for sure whether people are refusing to call the police more often when a crime occurs because they don’t think the prosecutor will do anything about it. That said, I’m skeptical of this rationale for the simple reason that victims — like offenders — are more likely to think in terms of the swiftness and certainty of an offender getting caught rather than whatever outcome might occur in the criminal justice system when considering whether to report an offense.

If your car is broken into then your willingness to call the police may be influenced by the police taking an hour or two to respond. Or maybe it is influenced by your understanding that only a tiny percent of vehicle burglaries in your city get solved. Much further down the list, in my opinion, is your impression that if the perpetrator is somehow caught then there is only a coin flip (or less) chance that the prosecutor in your jurisdiction will accept and prosecute the charges in the next 9 months.

Both perpetrators and victims likely know that clearance rates for property crimes are usually pretty low throughout the country. Going back to Seattle, the theft clearance rate in 2022 was reported at 3.1 percent. That’s up from 1.9 percent in 2021 but down from 5.4 percent in 2019.

Perpetrators and victims are less likely to understand the exact figures — unless they read this newsletter! — but my guess is they intuitively know the odds of an arrest for any one offense are low. Whether it went up from 2 percent to 3 percent from year to year probably doesn't mean much for offenders and victims. Moreover, the City Attorney in Seattle has been vocal about trying more shoplifting cases which would, in theory, lead to less underreporting if the role of the prosecutor was prominent in whether an incident gets reported.

Nationally, the theft clearance rate in 2022 was just 12.9 percent. It was 12.7 percent in suburban counties and 13.3 percent in rural counties. It was 12.5 percent in Pittsburg, Kansas, 10 percent in Pittsburg, California, 11.6 percent in Pittsburg, Texas, and 18.7 percent in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. And that's relative to the one in five thefts that got reported last year. In other words, only a tiny percent of thefts make it to the desk of a prosecutor no matter where you live and what the prosecutor plans to do about it.

If underreporting is increasing, and that’s a big if, then I would think that clearance rates (which have been low and falling) are playing a substantially larger role than the charging decisions of a handful of local prosecutors. But my guess is that these low clearance rates are already baked into peoples’ decisions on whether to report a given crime so the declines since 2019 probably had minimal, if any, impact.

Conclusion

To finally answer the initial question, I would say that the changing crime trends shown in the FBI preliminary data are preliminary and undoubtedly imprecise but likely reasonably accurate. They are imprecise because the year is not complete, the reporting is not finalized, and only around 80 percent of the US population was represented in their data. The data we get 10 months from now may show smaller decreases or even small increases and we shouldn't be shocked to see that because of the preliminary nature of the data.

The problem with automatically claiming the national crime trend is getting worse solely because underreporting is worsening is that it creates a situation where the trend can never go down.

It's already problematic to base our understanding of crime trends on anecdotal readings of reported incidents (I think crime is up because I saw a bunch of robberies reported on the news). It's much worse — in my opinion — to base one's impression of the trend on anectdotal readings of unreported incidents (I heard about some incidents that didn't get covered so it can’t possibly be getting better).

Crime data is inherently flawed, but I would personally put increasing underreporting at a national level way down on the list of reasons to be suspicious of the observed crime trends. They are likely accurate even if we won’t know the final numbers for a while.

Thank You very much for this! Your take on what can be gleaned from the NCVS was more or less where my thinking had taken me, but I have more confidence in you than myself on these things. :)

In your last paragraph, you wrote: "Crime data is inherently flawed...", and that made me think of the quote attributed to George Box - "All models are wrong, but some are useful". Crime data, like any data can be useful, even though it can never be perfect.

7 percent of identity thefts are reported to law enforcement per BJS. Do we create policy based on the 7 percent? Crimes reported to law enforcement are filled with endless problems which is why we have the National Crime Victimization Survey (which is routinely ignored).

Per the FBI's data from 2022 and their slight decrease in violent crime, we all recognize that violence "may" have gone up considerably for a multitude of reasons, underreporting may be the tip of the iceberg. I just did an article on family members and non-strangers being responsible for most violence. How many of these events were reported? I'm guessing that the number is quite low. It's the bulk of violent crime.

Yet crimes reported to law enforcement is the hand dealt, warts and all. It's all we have beyond the ignored National Crime Victimization Survey. There is a point where if crime statistics do not show a clear pattern of increases or decreases, does it really count?

As always, thanks for your analysis. You do great work. But I believe that we need to rethink what we report and how we report it while understanding that the caveats would be endless.

An example: Vermont (via the Associated Press-today) is reporting a huge increase in violence in one of the lowest crime states in the country per FBI numbers. Small numbers allow for large percentage increases or decreases. Yet that wasn't mentioned.